Mary Ann Spinelli

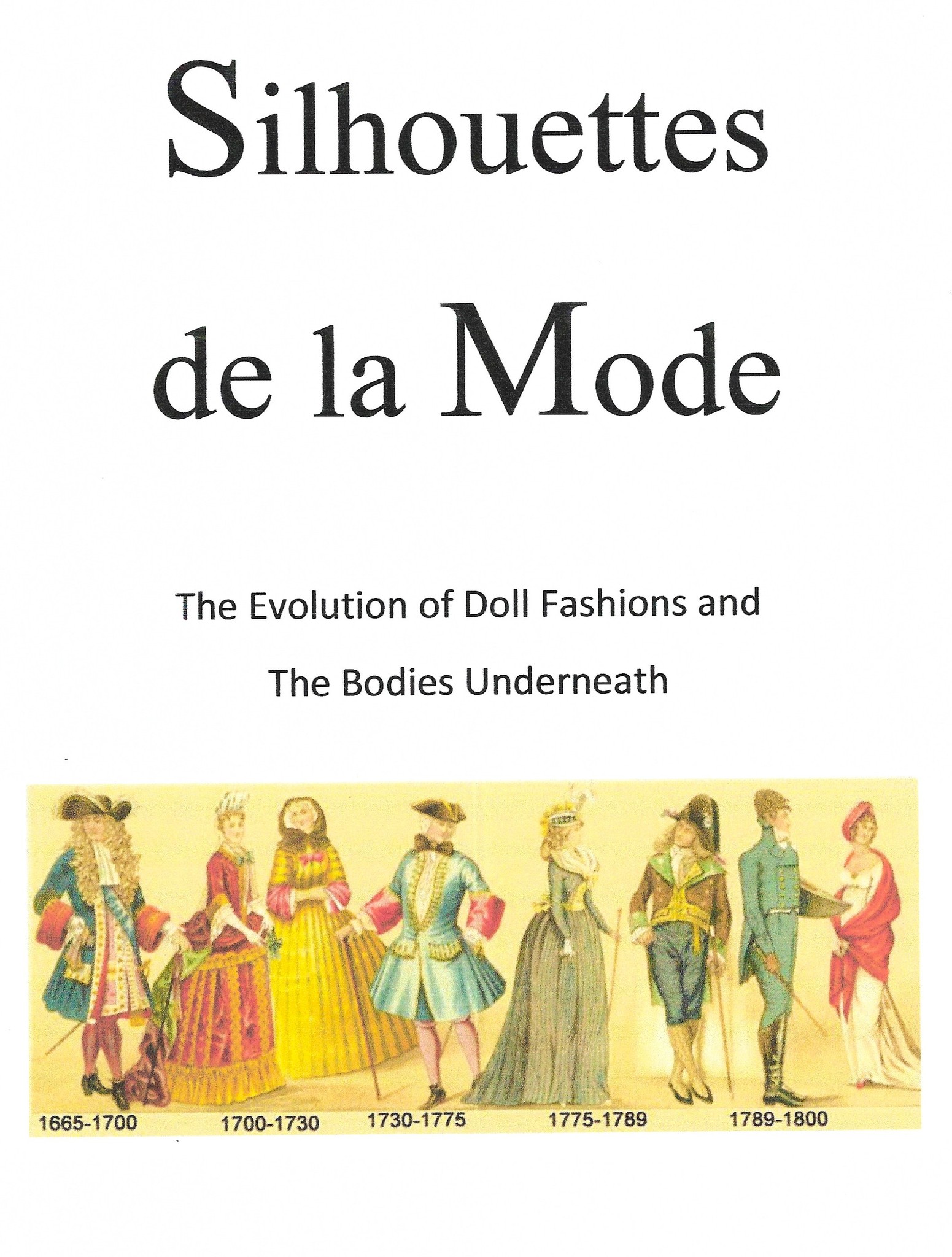

Silhouettes de a Mode, The Evolution of Doll Fashions and The Bodies Underneath

This will be a study by decades including the 1770’s through the 1920’s. We begin today with the 1770’s.

The style of Women’s garments in the 18th Century reflect the improving status of women in society. While the mantua of the early 18th Century was a rather simple limp garment composed of two lengths of fabric pinch pleated at the waist with wide soft sleeves sewn in, the mantua was gradually stiffened, decorated and expanded with hoops called panniers until, by mid/century it had been stylized into the Robe de Francaise, a doll-cake-like structure that insured that a woman took up three times as much space as a man and always presented an imposing and ultra feminine spectacle.

After 1760, women began to expand vertically as well, raising their hair with pads and pomade to a height that only a man on stilts could hope to emulate.

Below are some of the fashions of the 1770’s.

We thought that you would like to see some dolls in early 18th century clothing through the 1870’s era.

The first image is from the Victoria and Albert museum collections. 1860’s doll, wooden, approximately 24 inches tall. She is wearing the following 18th century items: Cap (Headgear), Necklace, Sack, Petticoat, Engagement, Engagement, Mitten, Mitten, Stomacher, Chemise, Stays, Stays, Petticoat, Petticoat, Pocket, Pin Cushion, Stocking, Stocking, Shoe, Shoe, Fob Watch, Etui. The original headed pins suggest that the garments have remained in position since the 18th century. – Photo credit and information: V&A Museum.

The second image is of an 18th century gown in the Williamsburg Museum Collections. Note the panniers width on the gown. Photo credit: Colonial Williamsburg.

The third image shows Lord and Lady Chapham wooden dolls. They are early and their costumes are from the 1690’s to 1700. We are showing them so that the reader may see what the female costumes looked like prior to the later 18th century. Photo credit: V&A Museum collection.

A little more about 1770’s fashions..

“1770-1779”

OVERVIEW

1770s fashion simplified the earlier decades styles for both womenswear and menswear, leading to new fashions that exemplified the ‘casual’ aesthetic that had taken hold.

The 1770s marked a transition in men’s and women’s dress, particularly for daywear. The growing popularity of what had previously been considered informal styles along with the increasing use of wool, cotton, and plain, lightweight silks changed the look of masculine and feminine attire towards greater simplicity. For men, the overall line of the three-piece suit became slimmer with the coat skirts cut well away from the center front, tight-fitting sleeves, and narrow tails. For women, the robe à la française with its characteristic box pleats falling from the back shoulders to the hem gave way to the robe à l’anglaise with a fitted bodice, the robe à la polonaise, and the caraco, or jacket bodice, and petticoat combination.

WOMENSWEAR

In this decade, the generously trimmed robe à la française, or sack, ceded its decades-long dominance to other styles and was primarily worn for formal wear (Figs. 1 & 2). At the same time, the hoop, which had given the robe à la française its distinctive shape, “disappeared except for court” and was replaced by “small paniers, or hip pads” (Ribeiro 222). The fitted gown, known in France as the robe à l’anglaise, had been worn in England throughout the century, alongside the sack as a more informal garment, and “in the 1770s, it had a new lease of life with a closed front opening” that obviated the need for a separate stomacher (Ribeiro 222) (Figs. 3 & 4). Initially, the back panels of this gown were stitched down as far as the waist and continued into the skirt; by the 1780s the bodice and skirt would be cut separately (Ribeiro 222). The oval-shaped sleeve ruffles accessorized with lace engageantes that had been standard since the 1740s were replaced by ruched cuffs, called “sabots” in French, of self-fabric, muslin, or gauze that fitted closely around the elbow (Figs. 3-6). Like the robe à la française, the robe à l’anglaise was worn over a matching or contrasting petticoat (Figs. 3 & 4).

One of the most popular styles from the mid-1770s to the mid-1780s was the robe à la polonaise (Fig. 6). Dress historians Kendra Van Cleave and Brooke Welborn have charted the appearance of this two-piece gown in contemporary fashion periodicals and other publications, including fifty-nine plates in the Galerie des Modes that illustrate the robe (full-length), carcao (hip-length jacket), and camisole (short jacket) à la polonaise (Van Cleave and Welborn 2). As they note, in addition to the distinctive swags created by looping up the skirt with interior ribbons or cords that were “attached on the outside of the gown at or below the waist,” the polonaise “was in fact equally distinguished by the cut of the robe” with two front and two back pieces “cut without a waist seam” (Van Cleave and Welborn 4-5) (Figs. 6 & 7). While the petticoat of the robe à la française and the robe à l’anglaise was only decorated across the front opening where it was visible, the exposed hem of the polonaise petticoat was fully trimmed (Figs. 6 & 7).”

By Michele Majer for her blog “Fashion History Timeline” for the FIT Museum, NYC, NY https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1770-1779/ Photo credits: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

After 1780, a fashion for Rousseauesque naturalism took over and women adopted more “natural” looking fashions which still took up a considerable amount of space, but emphasized the natural sexual characteristics of the female figure with padded busts and bottoms and riots of cascading hair.

The images below show examples of the 1780’s gowns and hair.

All information and images credited to Mary Ann Spinelli.

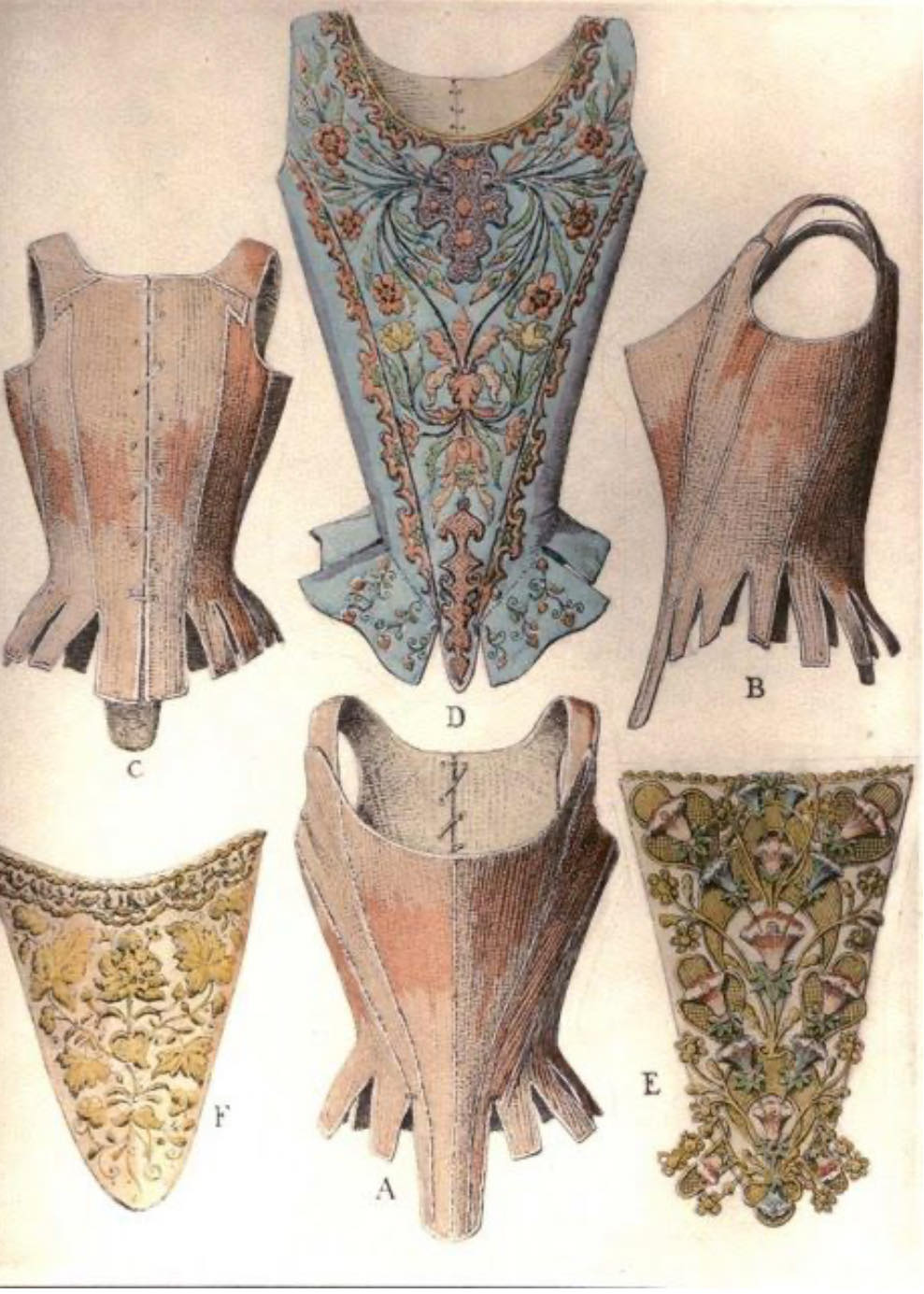

18th Century Provencal Undergarments

For a complete understanding of the fashion of the era, we must begin with a bit of history.

In pre-revolution France, there was a detailed series of classes. In Paris, it was even more so with eight distinct classes. This is based on Le Tableau de Paris, which was written in 1783:

“There are in Paris eight distinct classes; the princes and great nobles (these are the least numerous); the Nobles of the Robe (aristocrats); the financiers; the traders and merchants; the artists; the craftsmen; the manual workers; the servants; and the bas peuple (lower class).”

In other areas outside of Paris, there were generally three classes. (Four if you count the clergy who were an entity unto their own.)

The peasant class

The merchants aka working class

The nobility

Just like today different levels of income resulted in different levels of fashion.

Open drawers, later known as bloomers, weren’t really introduced for women until around the 1830’s. So what did they wear as underpants? Nothing. Tis true.

The chemise would be the first layer to put on. Bathing and washing clothing was not practiced as it is today so it was important to have a layer that would be changed regularly to protect outer clothing from body oils and perspiration. The chemise was often made from linen which is beautifully absorbent and allows the fabric to dry quite quickly. Chemises could also be made from wool, silk, or cotton but truly linen was the first choice.

A woman’s bust support came in the form of stays. There were a variety of stay styles and this is where class definitely becomes evident. The upper classes would wear stays that laced up the back since they had servants to dress them.

The under or interior petticoat was often made from a lightweight linen or cotton for summer.

It was not usual that the under petticoat would feature lovely embroidery even though it was not seen publicly. Quilted under petticoats could be worn for warmth in the winter. They were made primarily from silk or wool. But again, the fabric used would have been determined by the wealth of the wearer. Those of the lower classes would not have been able to afford silk.

If a bum roll was worn it would be the last thing to be added before the exterior clothing was added. Its main purpose was to act as a support under the exterior petticoat to create the desired silhouette of the time. They came in a wide variety of styles.”

The images below shown include 1880’s stays in both the upper class version and the working class version, petticoats, bum roll and a chemise.

Images and references from https://decortoadore.net/…/18th-century-provencal… by Laura Ingalls Gunn, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY.

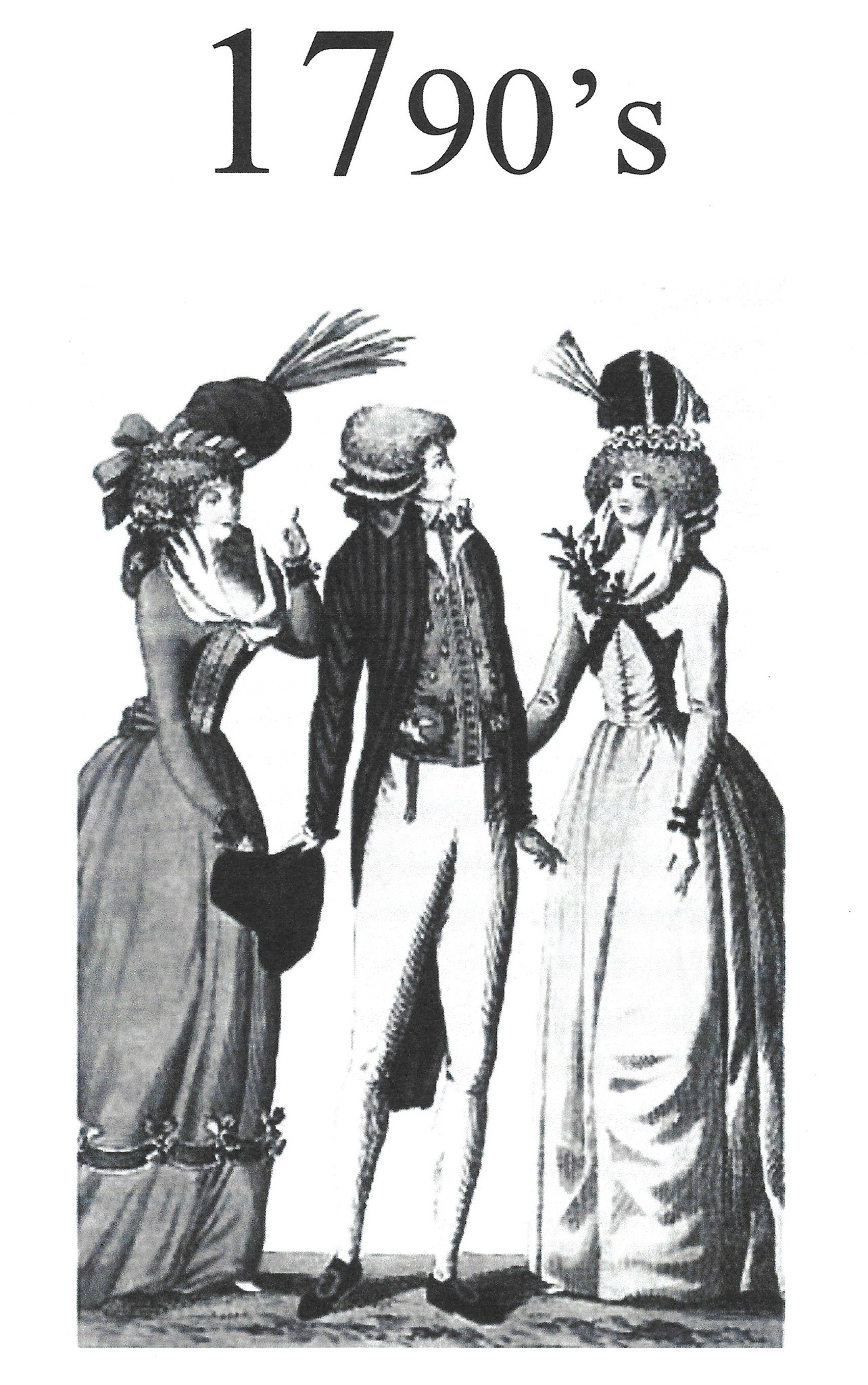

“The 1790’s saw women’s dress lose its artificially supported dignity in favor of comfort and naturalism. Not to be unnoticed however, late 18th Century women transferred their emphasis from splendor to sex and discarded not only their false rumps but their underwear as well. The woman of 1800 proudly displayed the strength of her femininity with as much force as her mid-century predecessor.”

Please observe the images below and see some of the subtle changes in the gowns and hairdos of the 1790’s.

The 1800’s…..

“The woman of 1800 proudly displayed the strength of her femininity with as much force as her mid-century predecessor.”

‘Inspired by early Greek and Roman clothing, women incorporated draping techniques into their dresses and opted for fine white or light-colored fabrics.”

“The year 1800 heralded a new century and a new world. The fashion landscape had changed radically and rapidly; the way that women dressed in 1800 stood in stark contrast to the dress of a generation earlier. The wide panniers, conical stays, and figured silks of the eighteenth century had melted into a neoclassical dress that revealed the natural body, with a high waist and lightweight draping muslins. The origin of this garment was the chemise dress of the 1780’s, worn by influential women such as Marie Antoinette and Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. The chemise dress, in part, reflected a neoclassicism that was beginning to emerge in fashion. Interest in classical antiquity had been growing throughout the second half of the eighteenth century, following the excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum….However, it was the violently shifting politics at the end of the eighteenth century that spurred this style to the forefront. The French Revolution brought the old world hierarchy crashing down, forever altering dress during the 1790s. The new classical style, imitating the clothing of ancient democracies, seemed to be evidence of a political philosophy on the rise.”

Sources: Google Search, https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1800-1809/, Wikipedia.com, The Louvre Museum

Photos show examples of the fashions of 1800.

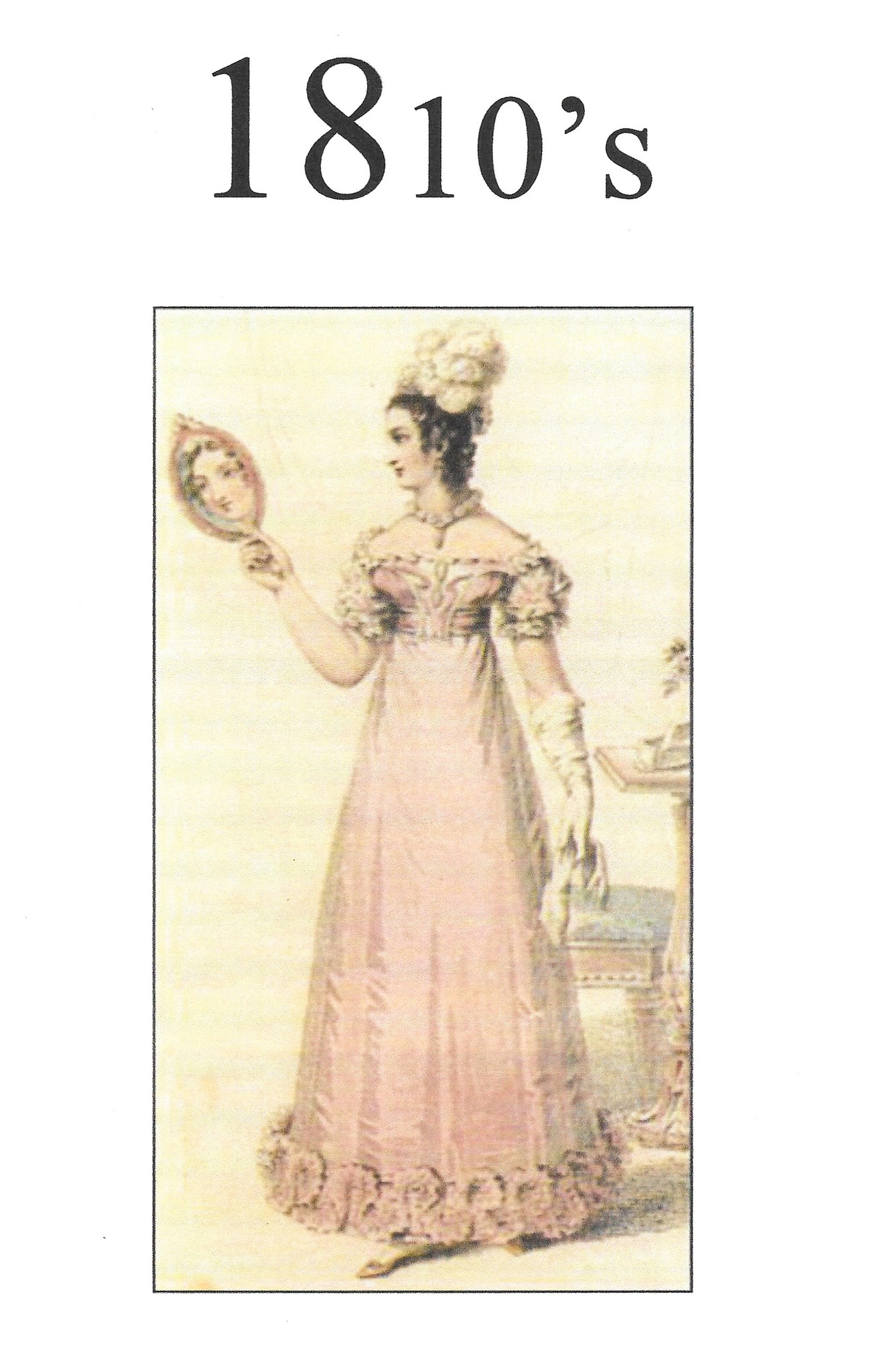

1810’s and 1820’s

“Necklines became squarer and adjusted by drawstrings, while the body became narrower. Sleeves remained above the elbow, with the length suited to the season or gown worn over the top. Though cotton had taken over for almost all other garments, white linen was still much preferred for underclothes.”

“The high-waisted neoclassical silhouette continued to define womenswear of the 1810s, as fashion remained inspired by classical antiquity. However, the purity of the line was increasingly broken by trim, colors, and a new angularity as tubular skirts were gradually replaced by triangular ones by the end of the decade.”

“The Pelisse can be a confusing term because there were several forms over a 50-year period. The first form of pelisse worn from 1800 to 1810 was an empire line coat-like garment to the hip or knee.

After 1810 it was worn full length and was a warmer longer-sleeved coat than the Spencer, but often made of the same materials. It was usually fur trimmed, straight in cut, belted at a high waist like the gown and sported a broad cape-like collar an influence of military styles. The colors for the pelisses were golden brown, dark green, and blue. The Pelisse was normally worn over pale gowns which were visible as it was worn open at the front.

From 1818 onwards women wore a coat dress variation called a pelisse-robe. It could be suitable for indoors or outdoors and was essentially a sturdy front fastening carriage, walking, or day dress.”

More to come!

References and Images”

Mary Ann Spinelli DOLL NEWS

Fashion History by FIT NYC edu.

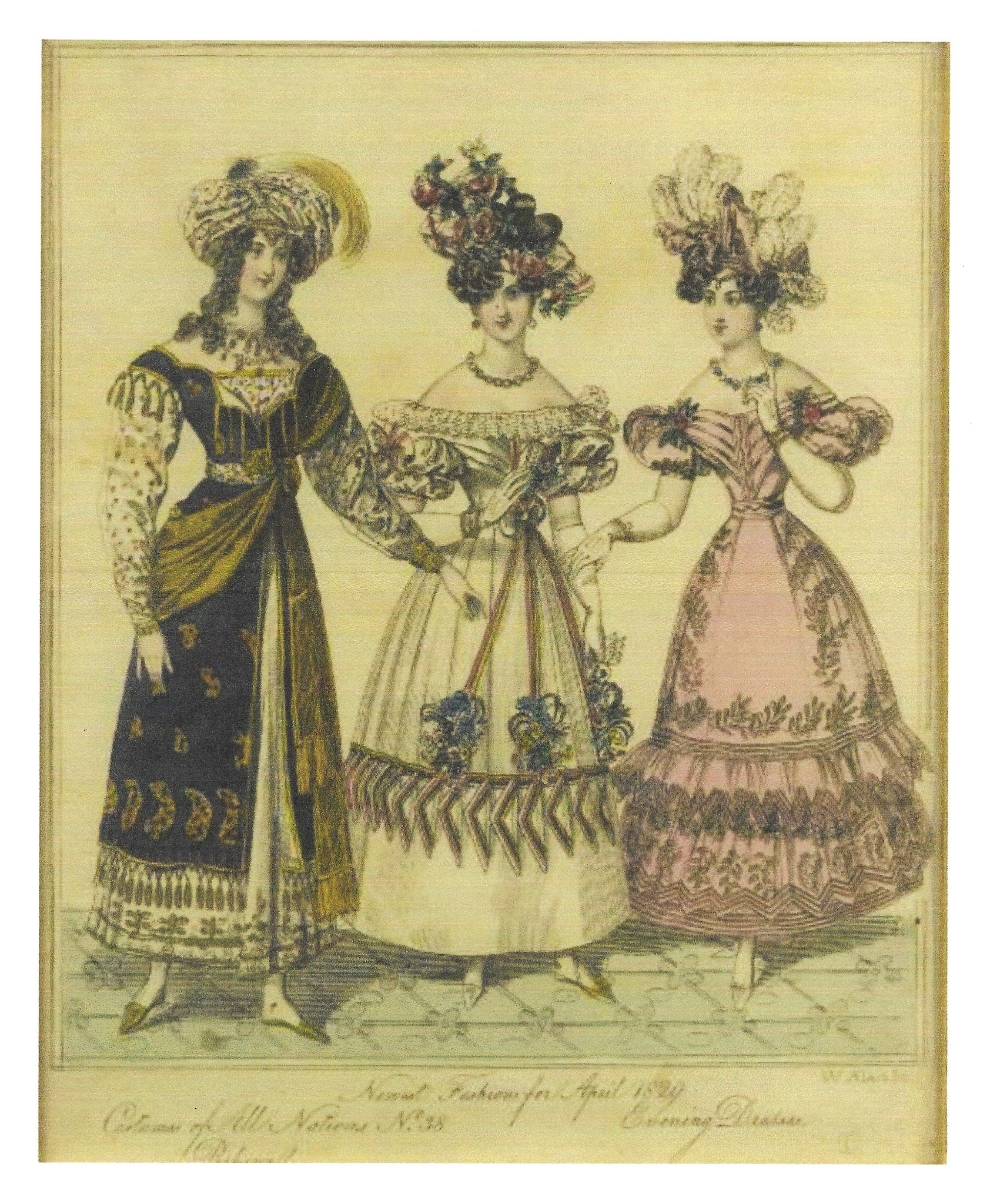

The 1830’s….

“1830s fashion was dramatic and overwhelming, marked by huge sleeves and hats, reflecting the Romantic movement. Extravagant dandies led the fashion world. After 1836, the exuberance that had defined fashion since the 1820s collapsed into a drooping sentimentality.”

The silhouette of womenswear abruptly shifted in 1836, and the fashionable woman was no longer one of ebullient energy, but a mild, modest woman who eschewed brash forms (Cunnington 105). This shift towards modesty was personified by the ascension of Queen Victoria to the throne in 1837. Despite her young age, Victoria preferred an understated, simpler style, and was cautious regarding new fashions. Her quiet modesty, piety, and maternal devotion to her family represented the ideal Romantic woman in many ways (Bassett 30; Byrde 46).”

The images below show the differences between the earlier 1830’s versus the later 1830’s under Queen Victoria’s influence.

References and images credit: https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1830-1839/

The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Los Angeles Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mary Ann Spinelli for DOLL NEWS

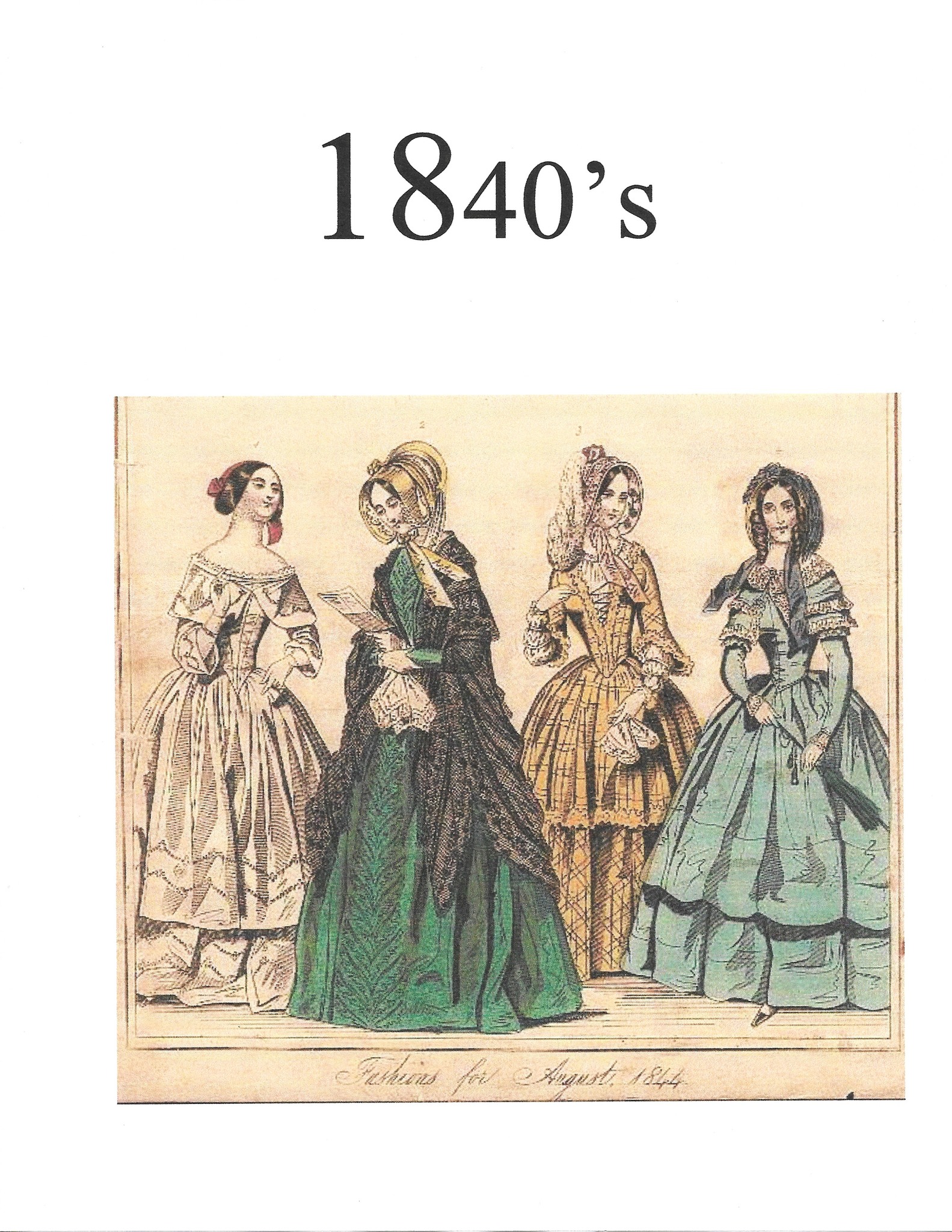

The 1840’s…..

“Restraint and restriction characterized the demure style of women’s fashions in the 1840s (Fig. 1). Fashion historian Jane Ashelford notes: Fashion illustrators no longer depicted the fashionable lady as a spirited and animated being, but rather as a timid, reticent and self-effacing person sheltering behind the ever-encroaching brim of her bonnet.”

Even the average woman of limited means was aware of fashionable trends due to the booming ladies’ magazine industry. In America, Godey’s Lady’s Book and Peterson’s Magazine reigned supreme, but French and English magazines could be found as well. The fashion plates published in these periodicals allowed all women to consume proposed fashions (Tortora 330-331; Severa 2-3).

“During the 1840s, women’s clothing was all hand-sewn, and had to be custom-made either at home or by a hired seamstress. While Elias Howe invented the lock-stitch sewing machine in 1846, it would not come into widespread use until the following decade. In general, all women had a sound understanding of sewing, and many items were made at home. However, as paper patterns were not yet widely available, and the complexity of 1840s dresses were difficult to achieve for an amateur.”

“The silhouette of the 1840s consisted of a long-waisted bodice, tight, narrow sleeves, and a full, dome-shaped skirt that now skimmed the floor. By the very beginning of the decade, the high waist of the 1830s had lengthened into a long, severely constricted torso marked by a bosom that was flattened and spread outward. This unnatural shape was achieved by a corset that ran from the breasts down over the hips, enforced with multiple channels of heavy cording and whalebone. Most importantly, all corsets featured a channel in the center front, into which would be placed a long, flat busk made of steel, wood, or whalebone. This rigid busk would run from between the breasts all the way down over the belly, preventing a woman from bending at the waist. Corsets laced up the back in this period.”

“Women wore their hair parted in the center, and looped smoothly over the ears, drawn back into a chignon or bun. An alternate style, worn especially by younger women for dressier occasions, consisted of long ringlet curls hanging on either side of the face, with the rest of the hair drawn back into a chignon.”

“During the 1840s and early 1850s, there was scarcely a more famous performer than Jenny Lind. A true celebrity, Lind was one of the first personalities whose name was used to sell clothing and accessories.Jenny Lind did not wear elaborate or flashy fashions as one might assume for such a sparkling celebrity; for her American tour, she performed in an understated white gown. In portraits, she is usually depicted in elegant, if simple and modest, fashions.”

More decades to come! We highly recommend that one reads more from the references listed. There is so much more information that we could not include here.

References. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1840-1849/ – 1840-1849 Posted by Harper Franklin | Last updated Nov 2, 2020 | Published on Mar 26, 2020 | 1840-1849, 19th century, decade overview, Ashelford, Jane. The Art of Dress: Clothes and Society, 1500-1914. London: National Trust, 1996. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/243850605 , Byrde, Penelope. Nineteenth Century Fashion. London: Batsford, 1992, Tortora, Phyllis G. and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume, 5th ed. New York: Fairchild Books, 2010. Severa, Joan L. Dressed for the Photographer: Ordinary Americans and Fashion 1840-1900. Kent, OH: Kent State UP, 1995. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Wikimedia, Library of Congress, The Cincinnati Art Museum, National Portrait Gallery, https://www.familysearch.org/…/1840s-fashion-victorian-age, Mary Ann Spinelli DOLL NEWS.

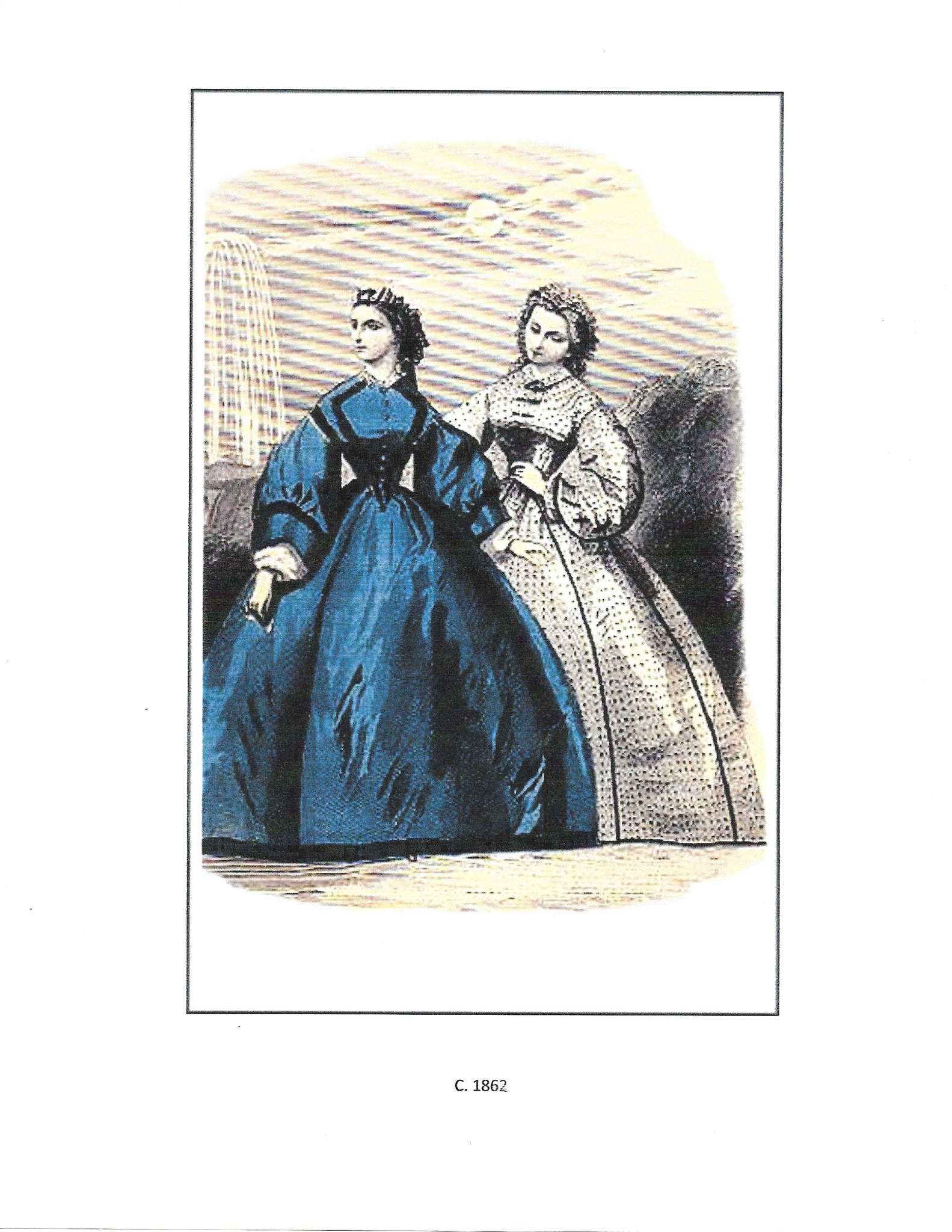

The 1860’s

The late 1860’s and early 1870’s saw a wave of nostalgia for the supposedly simpler times of the Regency/Empire/Federal era. This is reflected in the brief return of the empire waist, which sometimes looks a little odd when paired with cage crinolines and bustles, but I do love the early bustle period. Nostalgia for the early 1800’s would continue in the form of books, art and postcards.

“The silhouette of the 1860s was defined by the cage crinoline or hoop skirt, a device that emerged in the late 1850s, consisting of a series of concentric steel hoops attached with vertical bands of tape or braid (Cumming 37). Eliminating the need for multiple heavy petticoats to achieve the fashionable wide skirts, cage crinolines allowed skirts to reach their largest circumference around 1860 (Laver 188). Hoops were relatively affordable, creating a fashion that was worn throughout society and frequently the subject of withering ridicule as women’s skirts took up ever more space on sidewalks, benches, and halls (Shrimpton 13). Throughout the decade, the shape of the cage crinoline subtly changed, altering the entire silhouette with it. In 1860, it was huge, often measuring twelve to fifteen feet in circumference.”

“In the 1860s, a trend for skirts paired with shirtwaists, or blouses, as opposed to a matching bodice became prevalent for casual daytime wear, especially among young women. The most important type of shirtwaist was the “garibaldi” inspired by the military uniforms of Italian freedom fighter Giuseppe Garibaldi (Severa 197). Traditionally made in a scarlet merino wool with black braid and buttons, it featured a high neckline and full sleeves gathered into a tight cuff. The garibaldi shirt was also seen in black wool or white cotton (Cumming 90). Another military-inspired women’s fashion was the “Zouave” jacket borrowed from the Algerian Zouave troops who fought in the Italian war of 1859. The short, collarless Zouave jacket featured rounded borders trimmed in soutache braid, and fastened at the neck. It was frequently paired with a garibaldi (Cunnington 211; Tortora 366).

Technology and invention was evident in the fashion of 1860s women. Firstly, the use of the sewing machine grew exponentially, especially after the Civil War broke out in the United States instantly causing an enormous demand for ready-to-wear military uniforms (Tortora 358). The Singer Company, founded by Issac Singer in the 1850s, was the largest manufacturer of sewing machines in the world by 1860 and specifically created and marketed versions for domestic use (Brittanica).”

References and direct quotes: Mary Ann Spinelli DOLL NEWS,

https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1860-1869/, Theriaults Auctions Florence Theriault,

Photos: Mary Ann Spinelli Fashion Institute of Technology, Florence Theriault, Kyoto Fashion Institute, Royal Collection Trust, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Singer Through the Ages – Sewalot.com

1870’s Women’s Fashions….

“The first silhouette of the decade began in 1870; the great, circular or oval crinolines of previous decades collapsed into the so-called first bustle style. The bustle was a softly draped protrusion at the back of the waist, created by a manipulation of fabric and drapery (Tortora 386). This sloped bustle style was supported by horsehair-ruffled petticoats or crinolettes, an adaption of the earlier steel crinolines. A crinolette consisted of rows of fabric-covered steel half-hoops (Cumming 35; Shrimpton 17-18). Bustled dresses of this period were frothy confections, with layers of ruffles, pleats, and gathers. Many featured looped overskirts or long bodices that were draped up over the hips; these were often referred to as “polonaise” style dresses (C.W. Cunnington 261). Fashion historian James Laver quoted a contemporary writer who declared in 1876:

“it is now impossible to describe dresses with exactitude: the skirts are draped so mysteriously, the arrangements of trimmings is usually so one-sided and the fastenings are so curiously contrived that if I study any particular toilette for even a quarter of an hour the task of writing down how it is all made remains hopeless.”

“The first synthetic dye was invented in 1856, and by the 1870s, vivid, sometimes garish, colors were quite common and fashionable (Fukai 212). Bright purples, pinks, blues, and yellows could now be achieved with a vibrancy and permanence that had been impossible with natural dyes of previous eras. Frequently, a dress featured multiple colors, alternating between the bodice and trim, and layered bustle skirts (Shrimpton 19). Indeed, fashion historian C. Willett Cunnington wrote, “It is perhaps in their colors that the dresses of the ‘70s are most striking to the eye; the monochrome has vanished” (254). Trims became increasingly heavy as well; dresses were weighed down with flounces, bows, laces, tassels, braid, etc. All of these elements combined to create some of the most complex fashions of the century (C.W. Cunnington 255)”

References and direct quotes: https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1870-1879/

Theriaults Auction, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Musee D’Orsay Paris, Compilation of additional information by Billye Harris.

The 1980’s

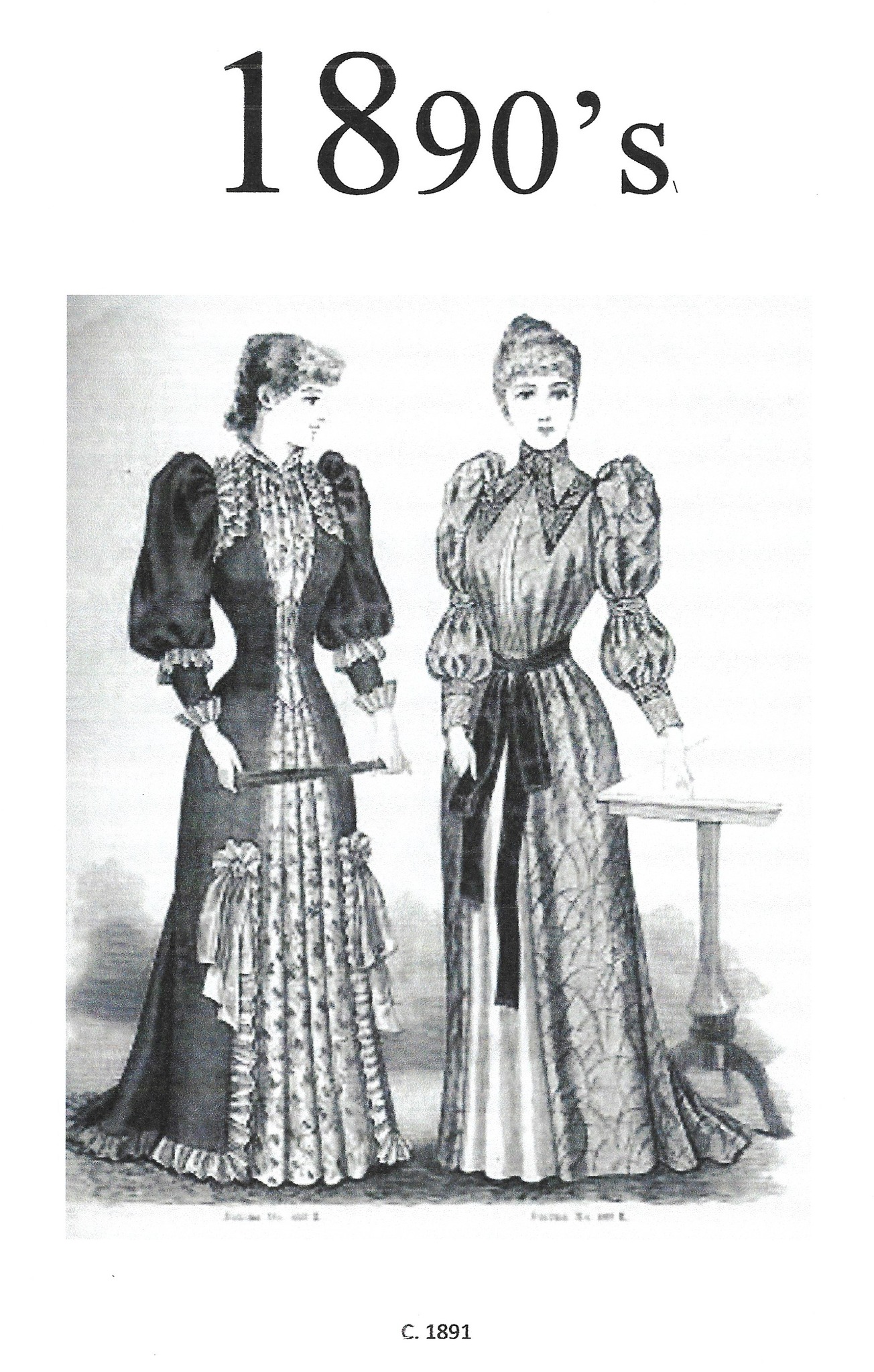

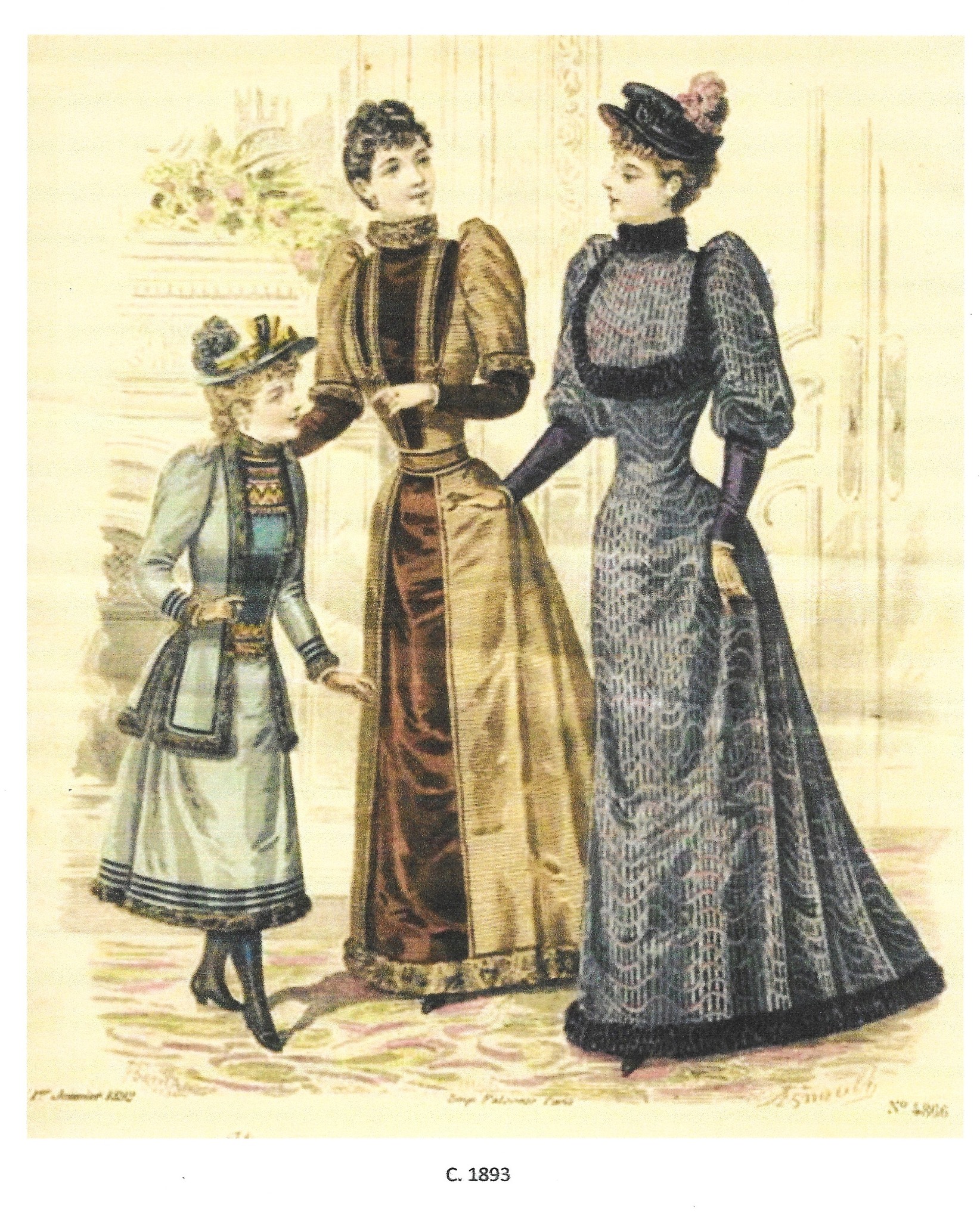

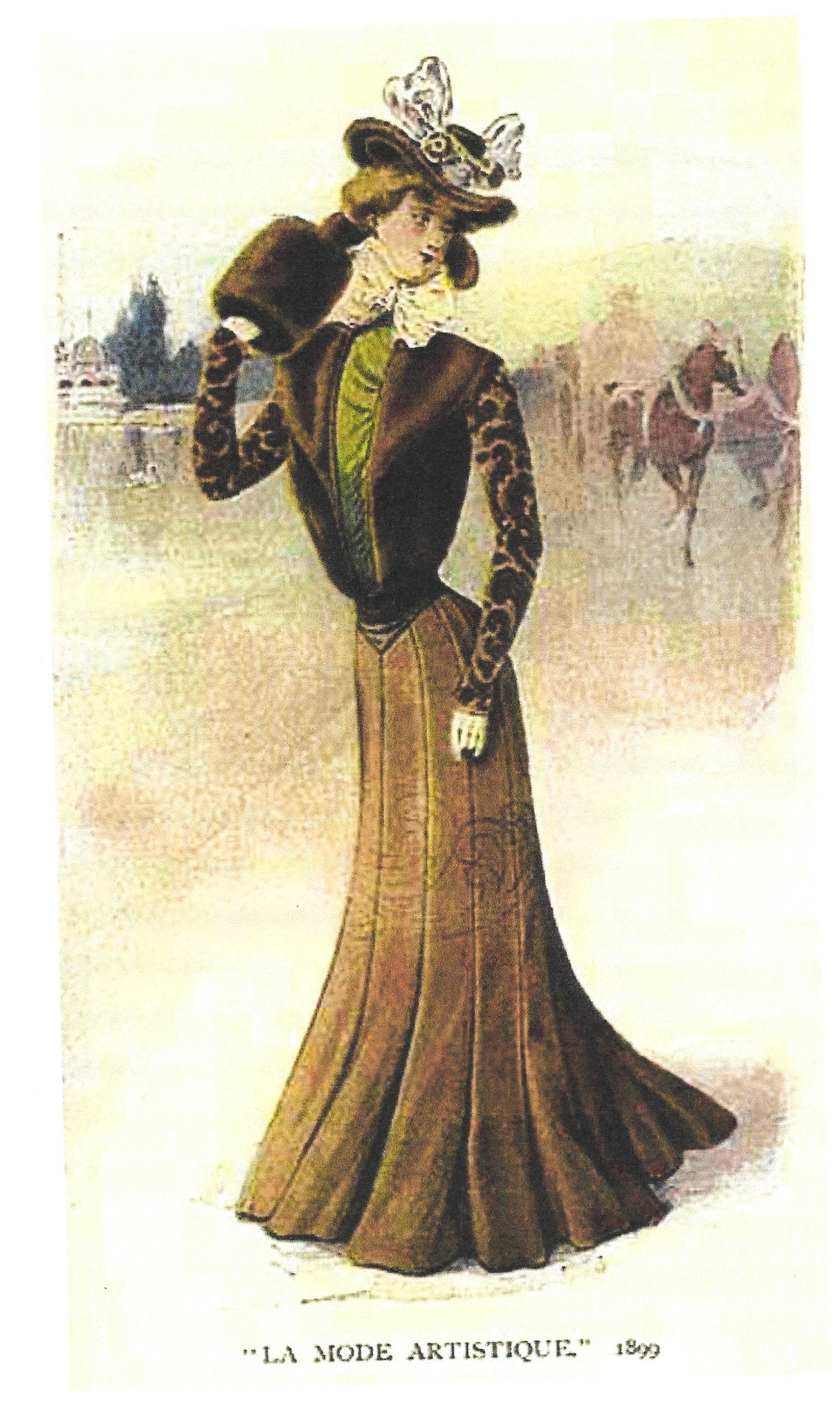

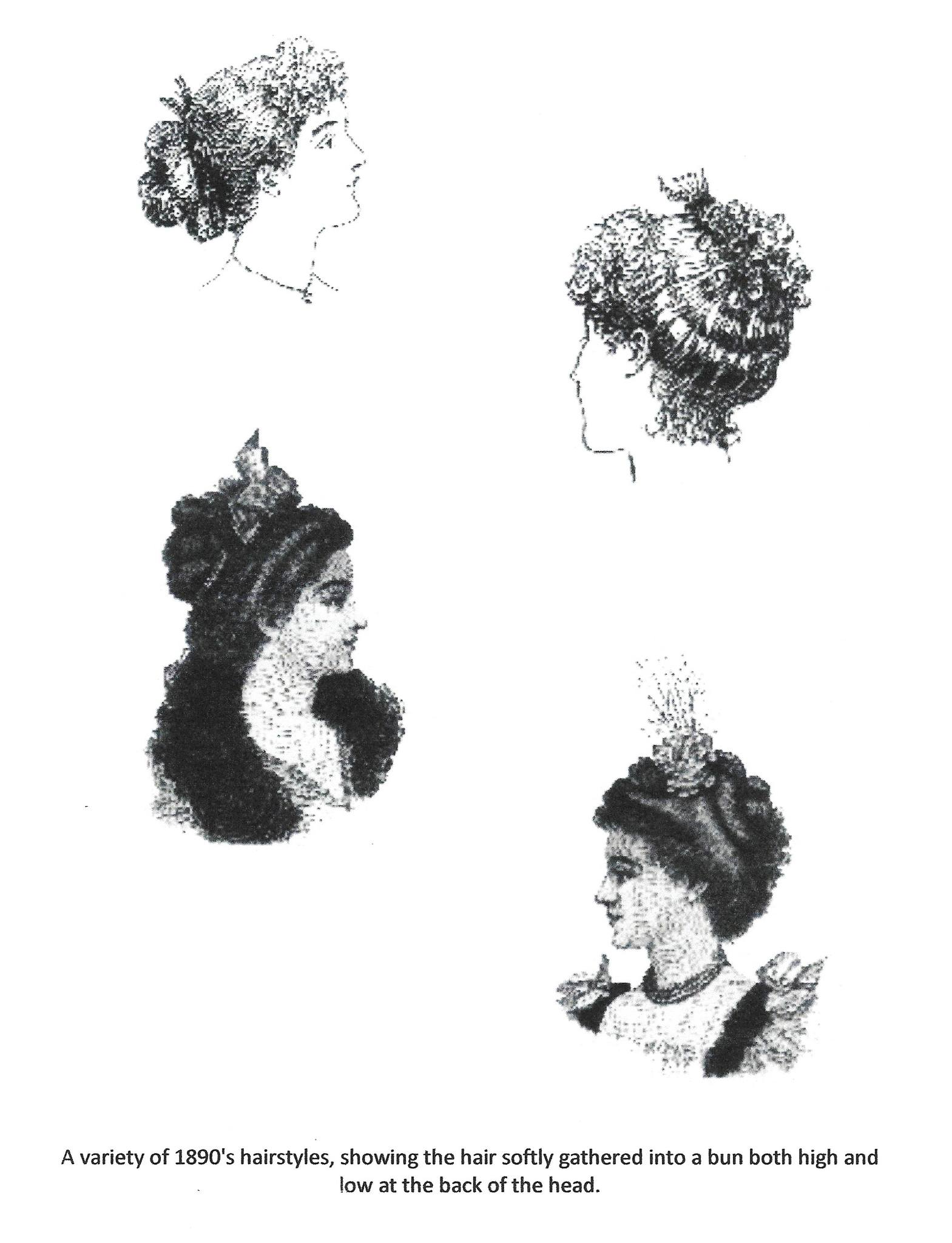

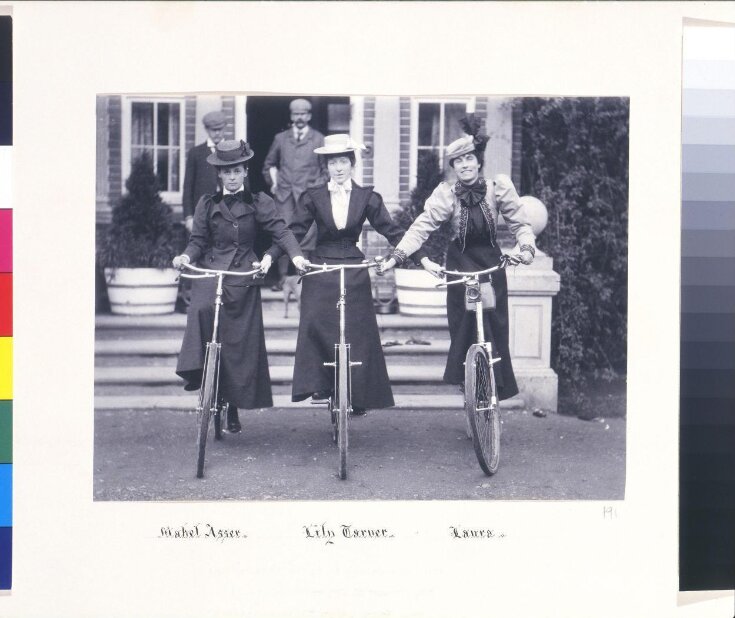

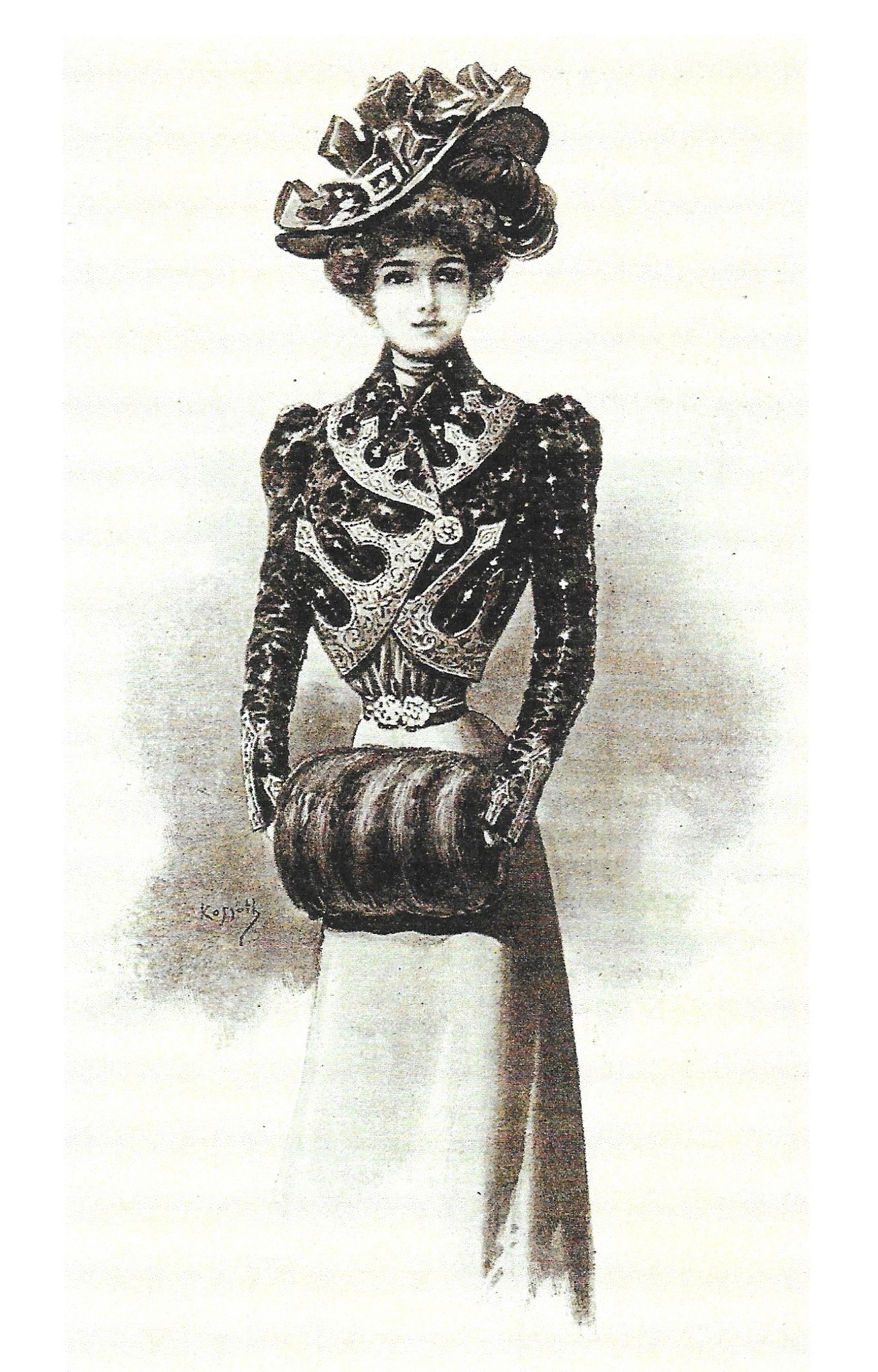

The 1890s were a period of change. As the century drew to a close, the world began to move away from the stiff, moralistic, Victorian Era (Laver 211). Urban centers were growing, and new technologies, such as the introduction of electricity into clothing manufacturing, produced a boom in the ready-to-wear market. Women were enjoying new levels of independence; during the decade the number of women employed outside the home almost doubled (Tortora 380-382). The “New Woman” of the era was an intellectual young female who worked, cycled, and played sports.”

“In the first years of the decade, the silhouette was a continuation of the late 1880s style, with the notable development of a small vertical puff at the shoulder (Severa 458; 476-481). By 1892, the dramatic, protruding bustle had completely disappeared, and the silhouette most associated with the 1890s took hold. Skirts were bell-shaped, gored to fit smoothly over the hips, while bodices were marked by the large leg-o-mutton or gigot sleeves. The early puff grew greatly in size, reaching an apex in 1895. The width at the top and bottom of the silhouette was balanced by a nipped waist, to create an hourglass effect (Tortora 397; Shrimpton 26-27). Around 1897, the silhouette began to slowly shift with the introduction of the straight-front corset. Supposedly designed as a healthier alternative, these new corsets forced a woman’s chest forward and hips backward into a curvilinear “S” shape, that became the dominant silhouette by 1900 (Laver 213).”

“Culture in the 1890s was swiftly changing in Western countries, as the turn of the century saw a shift away from rigid Victorian ideals. 1890s fashion allowed for more self-expression, particularly for women as gender roles became more flexible. As more and more women began working, cycling, and participating in sports, clothing began to reflect those changes. “

References and Photo Credits:

Mary Ann Spinelli for DOLL NEWS, https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1890-1899/, https://www.familysearch.org/en/blog/1890s-fashion-changes, Kyoto Fashion Institute, The Victoria and Albert Museum, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Museum.

1900….

The trends that marked 1900-1910 fashions reflected a significant turning point in history and style. The end of the Victorian era and beginning of the Edwardian era, this period reflected the manner in which men’s and women’s clothes were losing a little of their rigid formality and becoming more useful.

An important aspect of 1900 to 1910 fashions is the change of technology across many countries. The Industrial Revolution was in full swing and cloth could now be mass produced. This led to clothing that could be mass produced, which was an entirely new fashion concept. People no longer had to make their clothes themselves or rely on a seamstress or tailor. Some outfits could be bought off the rack for the very first time.

Women adopted a simpler fashion form from 1900 to 1910 than they had done in previous years. Restrictive corsets and high collars relaxed slightly. Dresses were still the standard, but they no longer needed to be puffed up around the hips with petticoats. Skirts became floor length instead of trailing.

One of the popular styles later in the decade between 1900 to 1910 was the hobble skirt. This skirt was somewhat full at the waist and tapered towards the ankles. Hats were still all the rage and the larger the better. It didn’t matter what your hat was decorated with, as long as it was decorated and big.

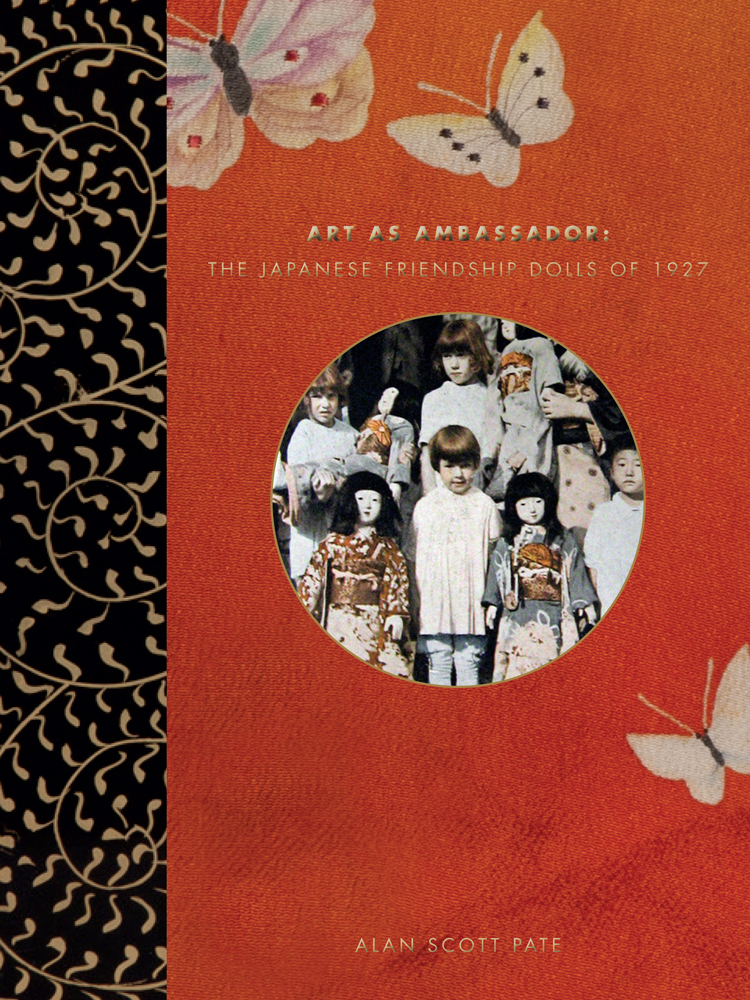

Allan Scott Pate

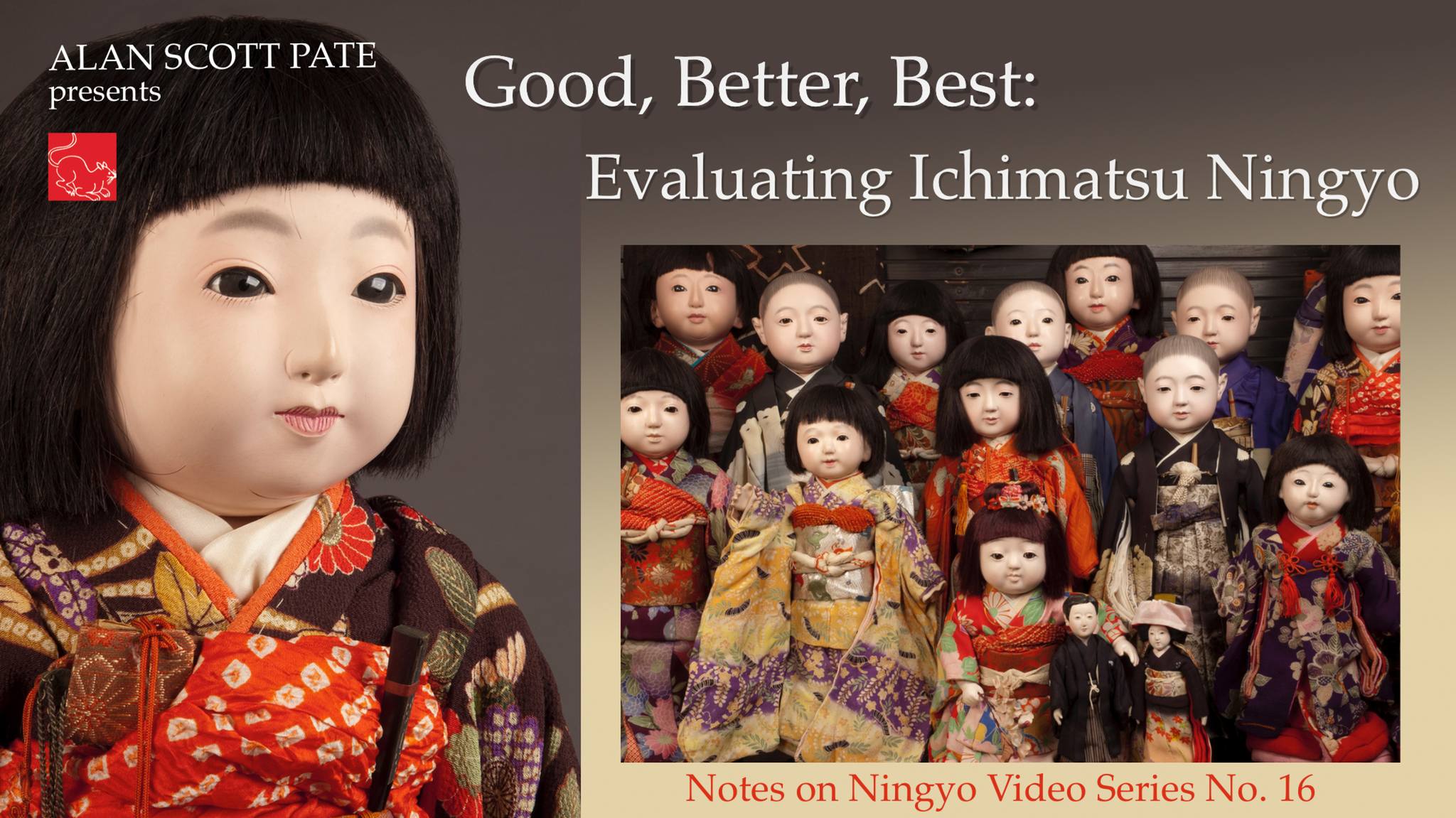

Good, Better, Best: Evaluating Japanese Ichimatsu Dolls

I want to thank NADDA for asking me to contribute to this important educational format. Every member of NADDA is committed to not only providing the best dolls in whatever genre they focus on, but also informing and aiding the larger doll community, adding their expertise to the general discussion. My particular area of focus and expertise is Japanese dolls, also known as ningyô. My one overriding mission since 1993 has been to expand the awareness of and appreciation for Japanese dolls; to present and explore the immense range of ningyô produced in Japan over the last several hundred years; and to help people better understand the nuances of this important category of doll. This is done through my participation in doll shows, curation a number of museum exhibitions highlighting the artistry of ningyô, guest lecturing at various events in the US and around the world, a YouTube channel presenting in-depth studies of various aspects of Japanese doll history and culture, and through the publication of a number of books focusing on the beauty that is ningyô. You can see some of this through my website www.antiquejapanesedolls.com

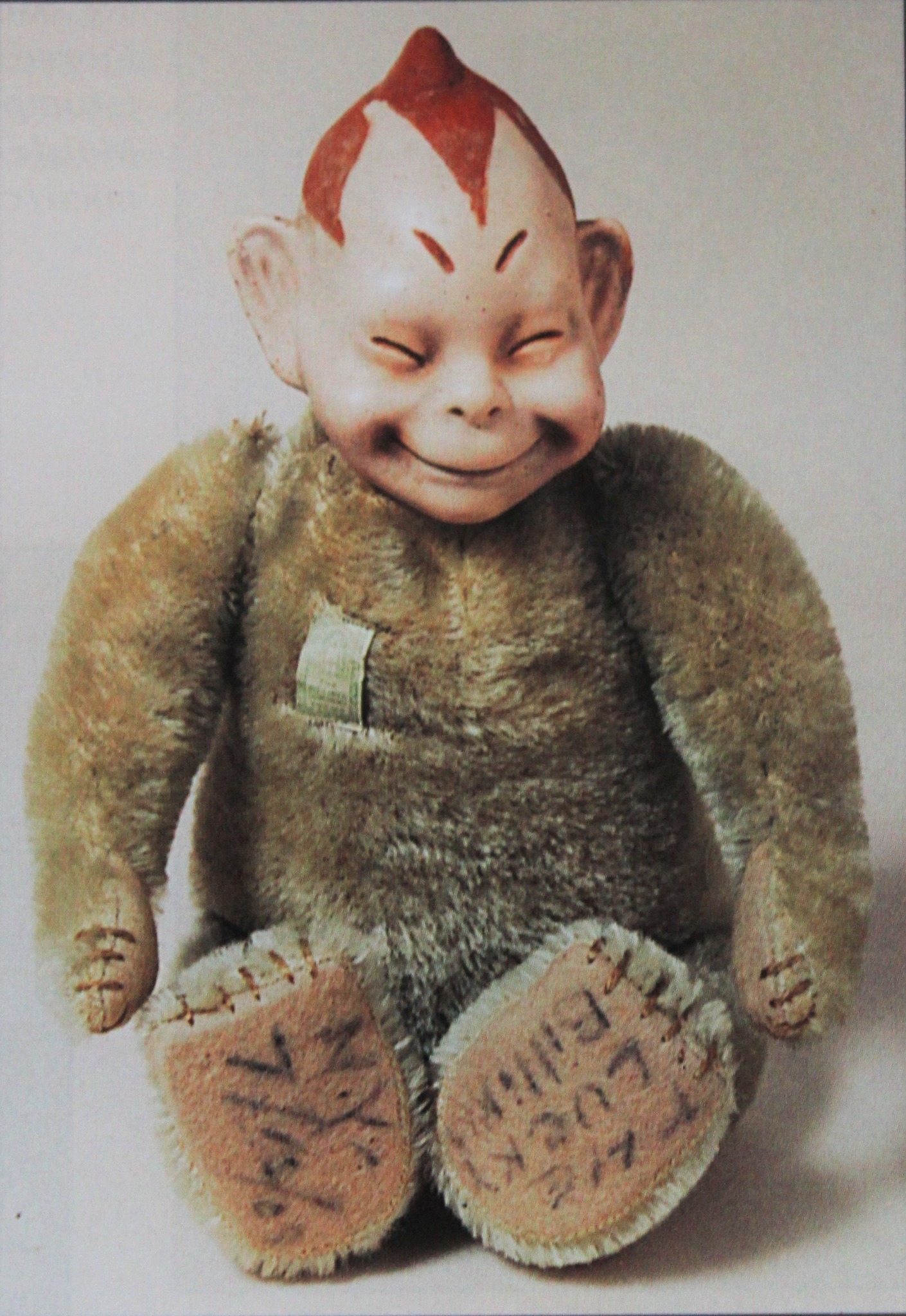

For too long, outside of Japan, Japanese dolls have been known primarily as a cheap souvenir doll, beautiful dolls in glass cases brought home after a military tour of duty, or a much-loved but over-handled play doll found in an antique market. While each of these has their value, this is such a sadly narrow view of the world of Japanese dolls. There is so much more to see, explore, and understand (and buy!). [Fig. 2]

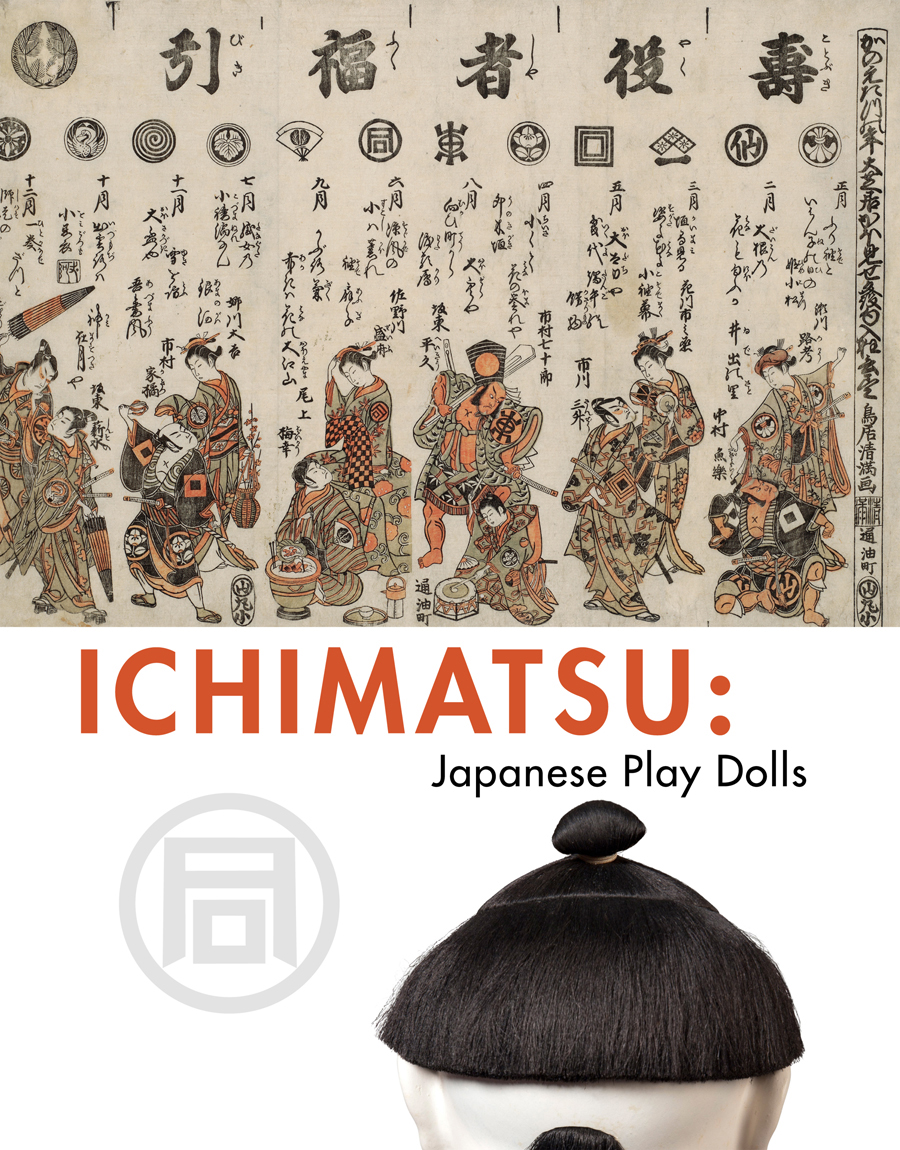

So in these pages, over the next few weeks, I want to take a deeper dive into one category of doll that will be familiar to many, but also elusive in terms of truly understanding and evaluating: ichimatsu-ningyô. I hope to provide a filter through which the doll collector can evaluate the ichimatsu they find or are offered and make intelligent, knowledge-based decisions on its merits. This is not really a difficult task once a few basic tips and key points of reference can be established. In shorthand, I refer to this as “Good, Better, Best.” [Fig. 2a]

Japanese dolls can be found residing in almost every doll collector’s home. Some are gifts received from a husband, father, favorite uncle or aunt stationed overseas. Some are delightful finds from antique fairs, flea markets and doll shows. Some are appreciated for their beauty, others more for sentimental reasons. Japanese dolls have long been a go-to gift for Japanese businesses to present to their American counterparts as well, and have therefore matriculated into many collections through more formal avenues. These dolls may be of magnificent geisha set in glass cases. Or perhaps an “emperor and empress” pair from the Hina Matsuri Girl’s Day display. They may be simple play dolls, lovingly worn and abused by the tender affections and ministrations of a distant, previous owner. Others may have merely caught the eye of the collector and were purchased for visual appeal and exotic intrigue as opposed to a fact-based rationale. One common denominator related to nearly all of these dolls, however, is a general inability of their current owners to evaluate them. Are they good dolls? Are they cheap souvenirs? Should they be insured? [Fig. 3]

What is a “good” doll? For many familiar with the wide range of categories within the Western doll world, there is a mental check list that one can go through to help in evaluating a doll already placed within a collection or when contemplating a potential purchase. People who focus more narrowly on a specific category will have an even more finely tuned set of criteria. This comes from years of experience collecting, seeing other examples that are held up or published as “good” examples of a given type of doll, as well as a large base of friends and dealers familiar with these dolls. So, in general, collectors can decide for themselves, or quickly determine, if a doll is “good,” “better” or “best.” Within the realm of Japanese dolls, this experience/exposure system seems to break down. This is largely due to a lack of opportunity for collectors outside of Japan to compare and contrast, to see why one doll is better or worse than another. This brief series is designed to h@Gailelp begin that process for at least one specific category of Japanese doll: ichimatsu.

In 1950, Albert Sacks published his seminal book on American furniture entitled: Fine Points of Furniture: Early American. He is credited with popularizing the concept of “good, better, best” as a basis for evaluating examples of a like type: Queen Anne Highboys, for example. It is an exceptionally handy tool and has been embraced by many, even in more traditional arenas of commerce. By comparing examples of Japanese ichimatsu we will begin to isolate the important elements to look for and how to combine these together so that a collector looking at a Japanese ichimatsu can decide if it is a good one, a better one, or a fantastic (best) one. The obvious question then follows: why not worst, better, best? I have always felt it better to train the eye by looking at the good stuff. Then the bad stuff will essentially sort itself out. There are five basic criteria points I look at when evaluating a Japanese ichimatsu: condition; face, hands/feet; textiles, and artist. For me, size is not particularly important. I am searching for the base quality of the doll itself. I have seen truly lamentable large-scale ichimatsu, and equally stunning smaller examples. Size is more a question of real estate allocation than necessarily intrinsic value. [Fig. 4]

Of course, each of these criteria can be used to evaluate to a certain extent other categories of Japanese dolls, from classic hina-ningyô used in the Girl’s Day display [Fig. 5]; to gosho-ningyô (palace dolls), those cherubic roly-poly boys (and girls) gift dolls Fig. 6]; to ishô-ningyô (fashion dolls) designed to delight the viewer through depictions of figures drawn from history and popular culture [Fig. 7]; to takeda-ningyô memorializing Kabuki theatrical performances [Fig. 8]; to the modern sosaku-ningyô (art doll) that emerged in the 1930s and continues to astound audiences today for their creativity and outside-the-box subject matter (Fig. 9)

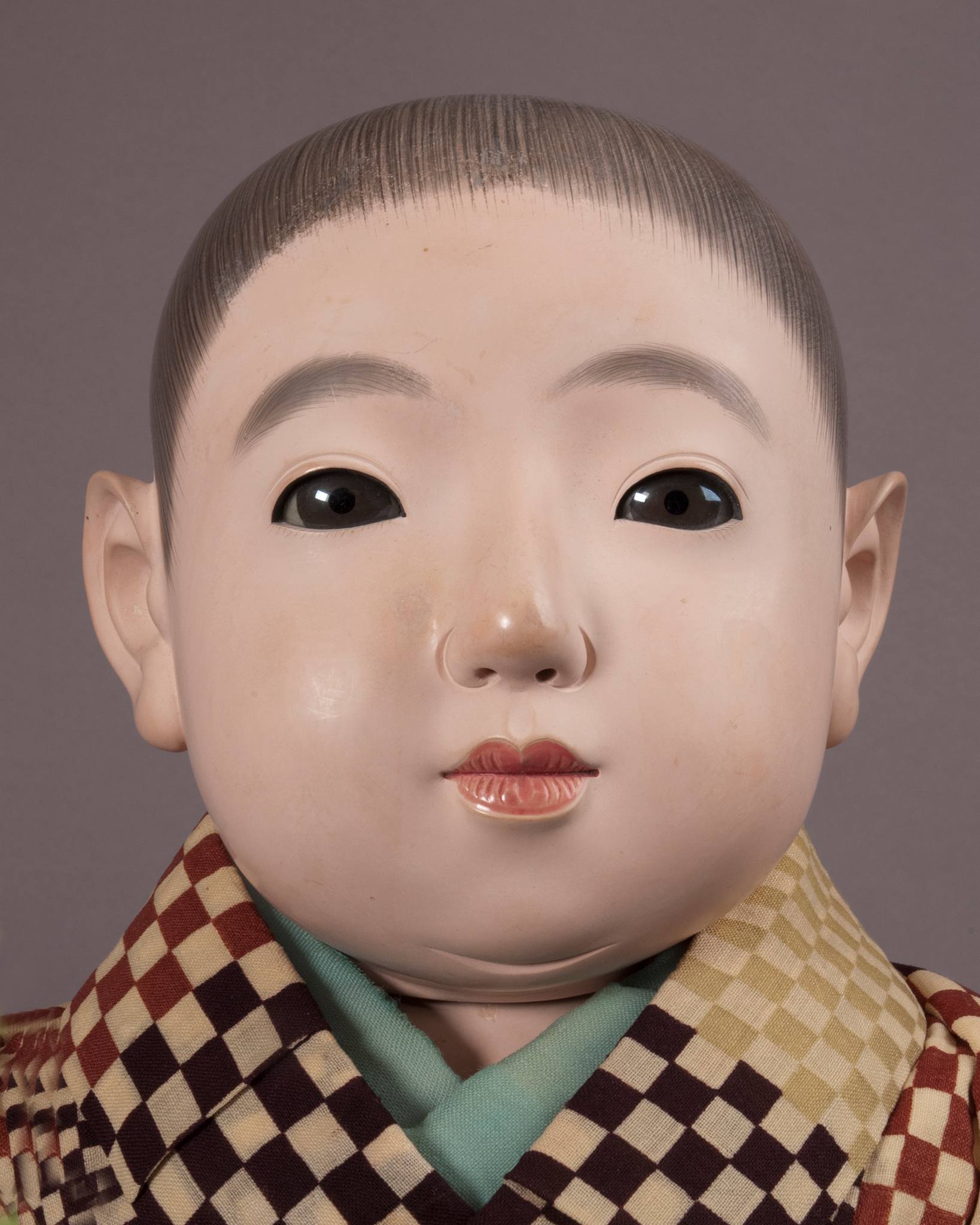

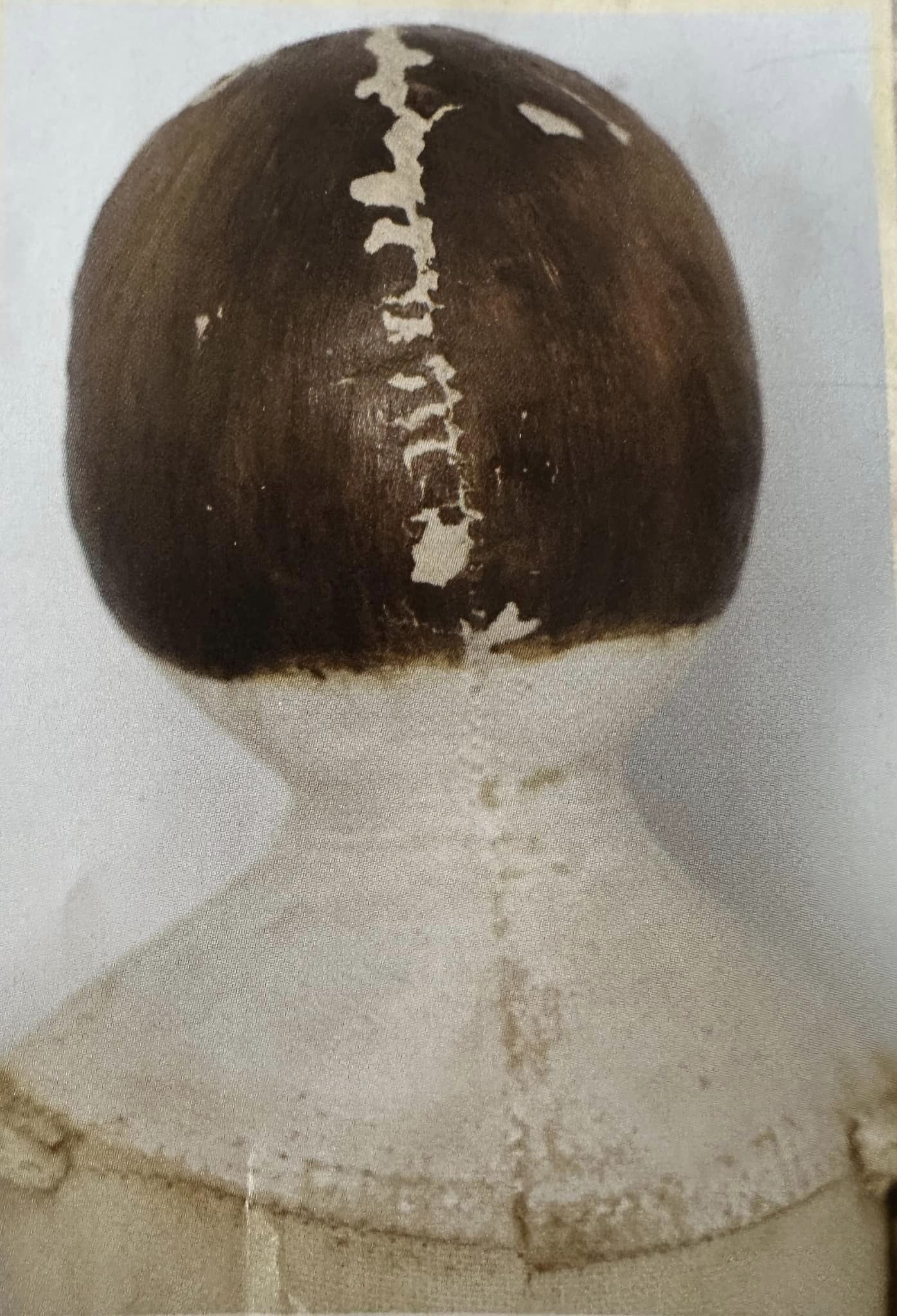

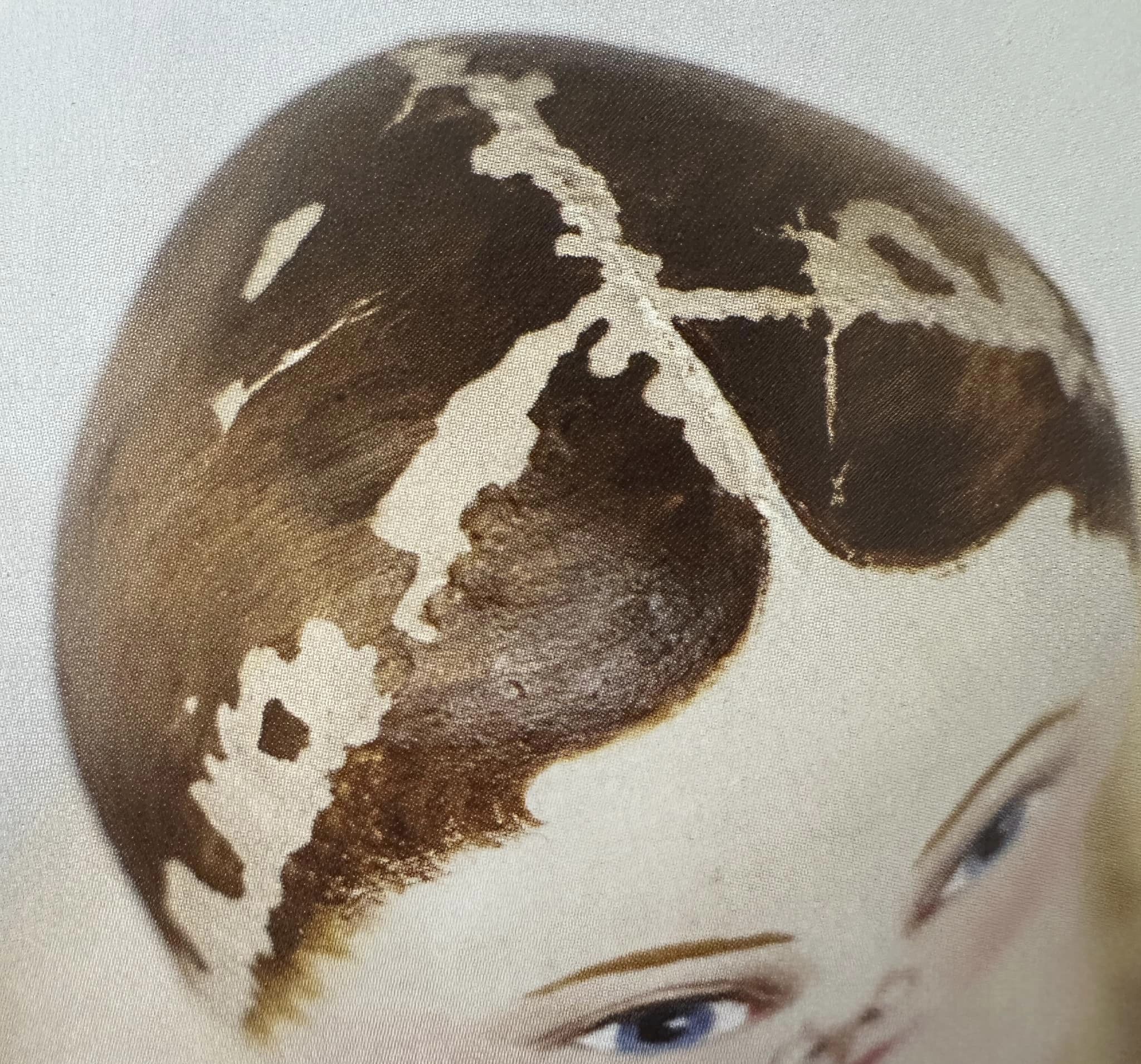

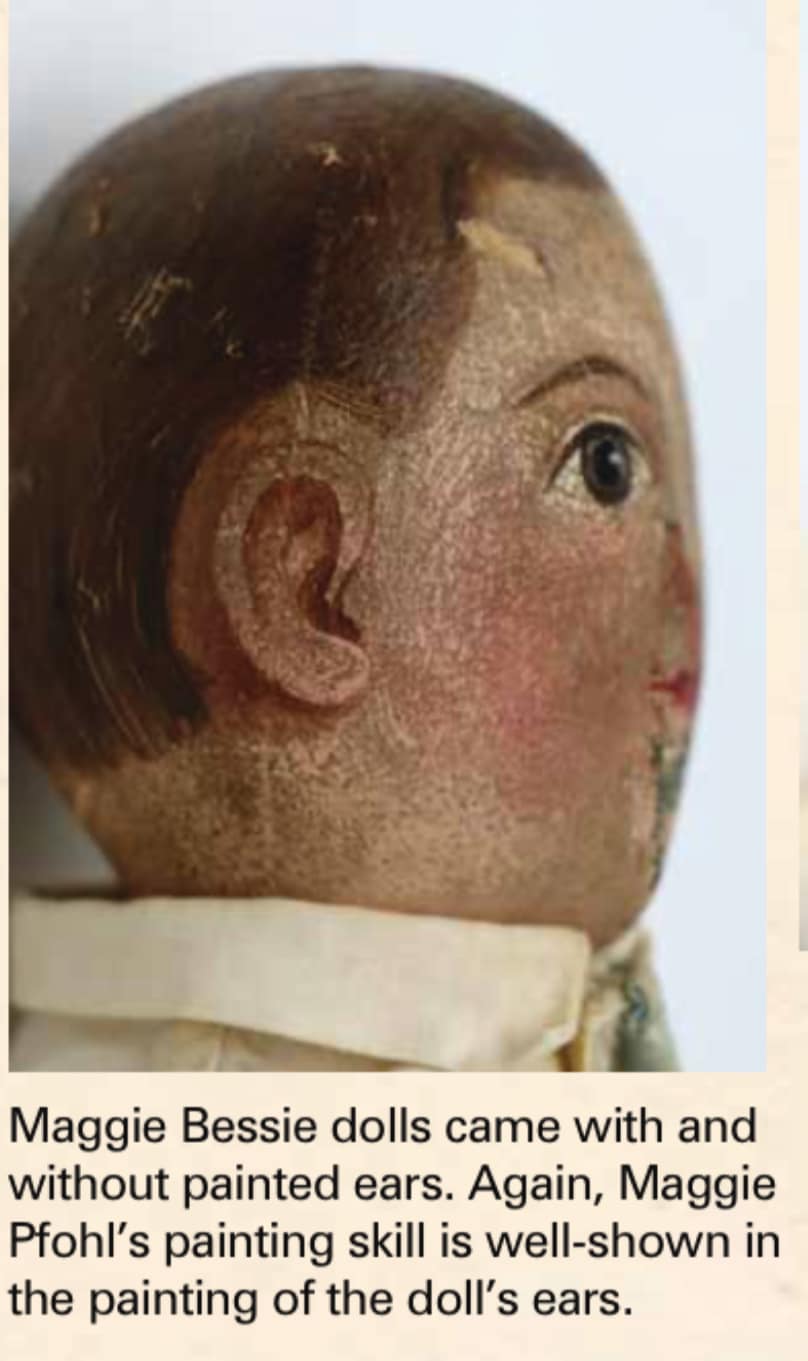

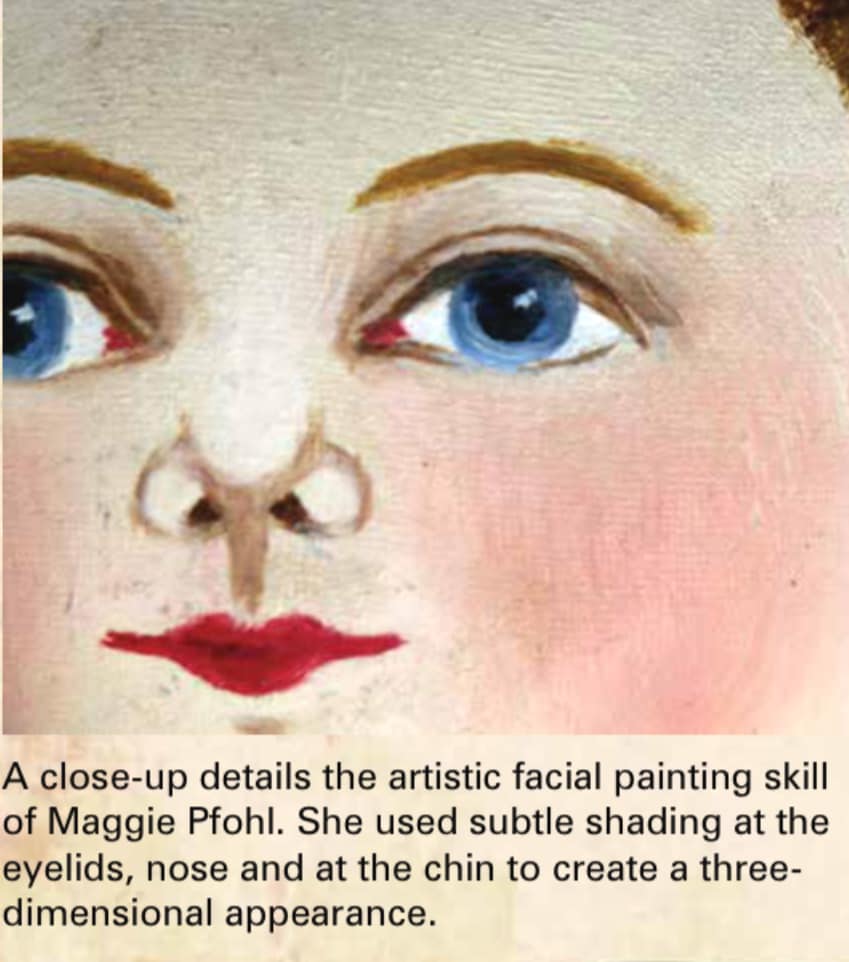

But let’s start with condition, which frequently for me is a full-stop before we even get out of the gate. Condition: This is perhaps the easiest category to understand and evaluate. After all, even for the most virgin collector, dirt is dirt. Frequently, however, dirt and soiling on a Western doll may not be a deal breaker, for bisque heads can be cleaned, some textiles can be readily replaced and the doll redressed. So while the initial condition may not be so attractive, the potential is there to recover the doll. With Japanese ichimatsu this is a much more problematic proposition. For example, the “skin” surface of most Japanese dolls is composed of a wood or wood composite sub-strata over which layers ofgofun (shell white) have been applied. Gofun is created through the mixing of pulverized oyster shell with animal glue. In its thickest iteration it can be worked, molded and sculpted. As it gets more finely attenuated it serves more as a skin coating that can appear porcelaineous, with a lovely sheen. Unlike porcelain, however, gofun is completely water-soluble. And while a bit of dirt or a fingerprint on a fine china head can likely be readily cleaned, cleaning gofun is not an easy maneuver, and for pigmented gofun, which attempts a more natural skin color, it is essentially impossible. Also, a bit of moisture on a cloth can strip away a hundred-year coating of gofun in seconds. So a soiled face on a Japanese ichimatsu is usually a “no-go” for me. Gofun is also prone to cracking, this is why the Japanese have over the centuries experimented with base materials: woods of different species, wood composite with different bonding elements, clay, etc. But not all cracking on a Japanese doll is equal. Usually I can look past a bit of stress cracking along the seams running along the sides of the head. These are typically obscured by the hair and also indicate that stress related to expansion/contraction of the substrata has already been dealt with by the doll itself in his/her own way. Mid-surface cracks, however, on the cheeks, forehead, etc, usually prevent me from moving forward and compromise the value, if not the very longevity of the doll itself. (Fig. 10)

Gofun is also prone to cracking, this is why the Japanese have over the centuries experimented with base materials: woods of different species, wood composite with different bonding elements, clay, etc. But not all cracking on a Japanese doll is equal. Usually I can look past a bit of stress cracking along the seams running along the sides of the head. These are typically obscured by the hair and also indicate that stress related to expansion/contraction of the substrata has already been dealt with by the doll itself in his/her own way. Mid-surface cracks, however, on the cheeks, forehead, etc, usually prevent me from moving forward and compromise the value, if not the very longevity of the doll itself. [Fig. 10]

Another area is the hair. Classical Japanese girl ichimatsu use human hair or silk wigs. But unlike Western doll wigs, which are largely designed to be easily removed, hair wigs for ichimatsu are firmly glued into place and removing them is a very aggressive procedure. Also, both the human and silkhair is more fragile than many Western doll hair types. Dry, aged hair cracks easily and simply can simply fall off the doll, while sunlight can give the originally black hair a red tint not easily remedied. [Fig. 11]

High-quality Japanese ichimatsu are generally not designed to be undressed and redressed. They usually are attired by the artist or atelier that made them, with careful attention paid to pattern and contrast between kimono and obi tie belt. Some dolls even have their clothes sewn on (kitsuke) which indicates that they are display figures rather than designed for play and changing of clothes. And while it is possible to find replacement kimono, or make replacement kimono (there are many books with doll kimono sewing and cut out patterns available in Japan), for the Western collector this might pose significant obstacles: sourcing fabric at a minimum, and tying an obi can pose challenges even for the Japanese. So a faded, soiled or worn kimono on an ichimatsu is also frequently a “no-go” proposition for me. [Fig. 12]

In short, as a general rule, Japanese ichimatsu must be evaluated on their condition, as is, not anticipating some wonder surgery or fashionable redressing. That said, some ichimatsu are so important, or so intrinsically beautiful that the restoration can be well worth it. But it is not an easy, or an inexpensive endeavor. One of the Friendship Dolls, Miss Aomori, was found in a sad state of repair, with extensive flocking and discoloration to the face, the hair was unevenly cut and damaged in parts, with extensive fading, damage and even the loss of a sleeve to her kimono. Essentially violating every one of the principals I have just laid out. But (!) as one of our original 58 ambassador dolls from 1927, she too important to let languish, and was well worth the conservation. So I took her back to Japan and had her treated by Iwamura Shôkensai III (Kenji, son of the original maker) and through a lengthy process she was brought back to her original glory. Well worth it! [Fig. 13, 14, 15, 16, 17] So condition; it is a starting point. But it is only the beginning….

Continuing our discussion of Good/Better/Best in Japanese dolls, we now turn to the doll itself, its personality and quality of execution by looking at the face as well as the hands and feet.

Let’s be honest, for most doll collectors, it’s almost always about the face! The face is what catches the eye. The face is what holds the attention. And the face is what we fall in love with. We look at them, and they look back. A bond is forged. A love kindled. A purchase made. We will overlook many other issues if we fall in love with the face. I know! I’ve been there!

So continuing with our evaluation of Good/Better/Best let’s talk about the face and how we can go about technically evaluating the gradations of quality and desirability in a Japanese ichimatsu-ningyô face, recognizing all the while that if we have already fallen in love, this is a secondary exercise!

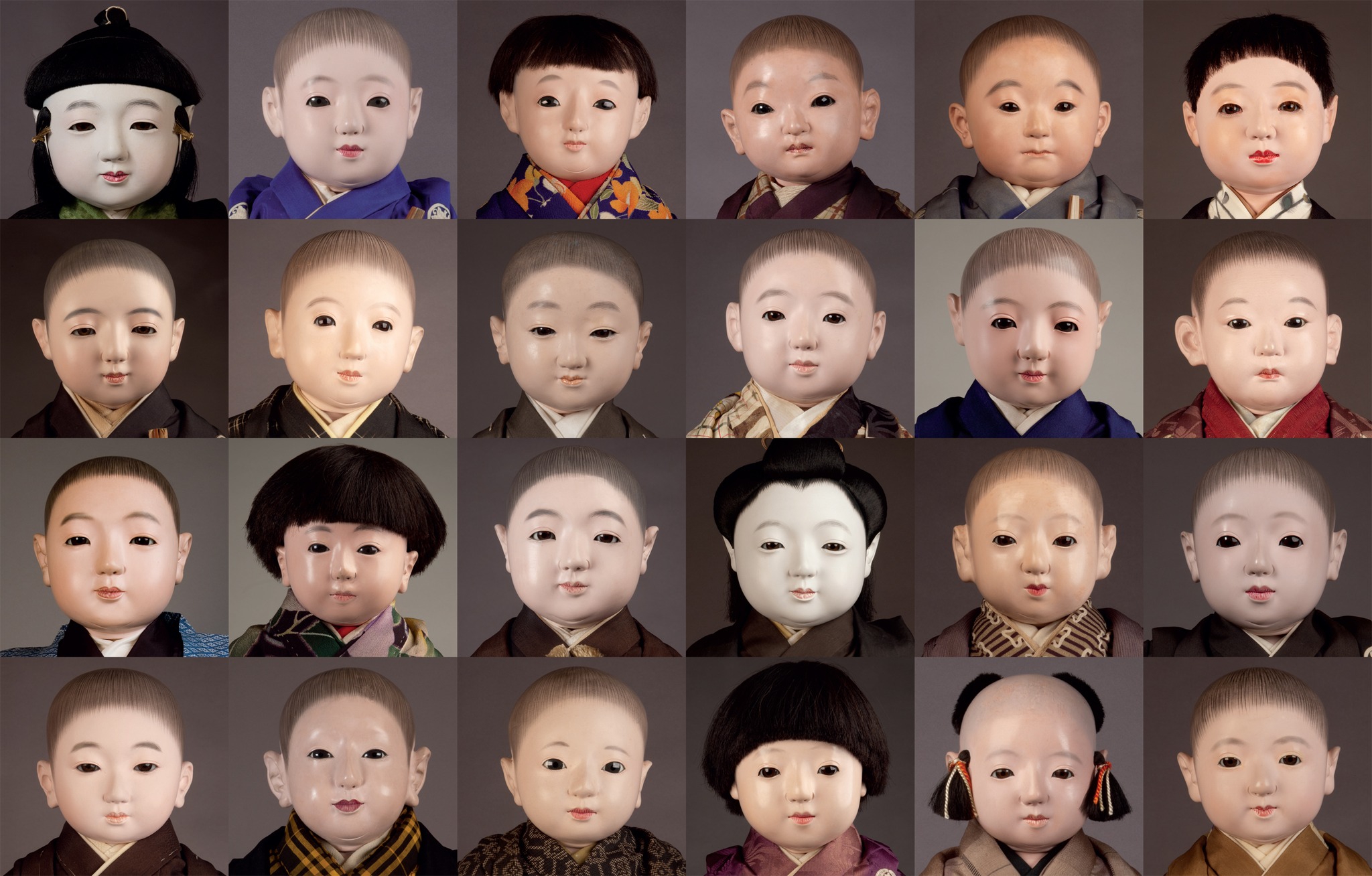

One of the most disheartening comments I ever hear (or read) about ichimatsu-ningyô is: “They all look alike”! Those 4 words actually hurt! When one becomes aware of the extremely complicated and time consuming processes that go into the creation of an ichimatsu-ningyô head and face, and begin to really compare one face with another, this first impulse of only seeing their similarities fades away and a deep recognition of their infinite individuality becomes clearer. [Figs. 18 ,19]

So let’s look at some faces!

Face: If our hypothetical ichimatsu has passed the basic condition requirement, clean gofun, no cracking or damage and a well-preserved kimono, we can start our evaluations in earnest. For nearly all doll collectors the face is perhaps the most important element of the doll. Do we love it? Are we drawn to it? Does it make us smile? Laugh? Cringe? It is natural therefore to begin with the face.

Unfortunately, for those unfamiliar with Japanese dolls and the specific qualities to look for, they tend to “all look alike”–narrowed eyes, black hair in an okappa shoulder-length banged cut. What is a good face? A better face? The best face?

Every Japanese ichimatsu is one of a kind. Unique. This is due to the process through which they are made. Although a mold is used for the head, this only creates the basic shape and size. All of the individuating features, from the fullness of the cheeks, the shape of the ears, the contour of the lips or eyelids to the depth of the philtrum, are all hand done, individually, by the artist through the skilful modeling and carving of the gofun surface. No two are the same. Thus these features need to be looked at carefully and not taken for granted. Good dolls will be pleasing, well balanced and skillfully rendered. Better dolls will have certain elements setting them apart, an open mouth for example, or more realistic glass eyes, or a greater depth to the carving. The best dolls, have all of this and more.

Take for example the three faces presented here. All are good. But if we look carefully we can see why one is good, one better and one best.

The first is a very “good” ichimatsu girl by Katsumitsu, a student of Takizawa Koryûsai II (1888-1986) [Fig. 20, 21, 22]. Her face is very well done with nicely shaped eyes and well rendered features. She has a bright, happy expression so endemic to the Koryûsai tradition, but here she is especially impish. The gofun is slightly pigmented intentionally to give her a more fleshly tone, but it is even and lustrous throughout.

Now compare her to a “better” ichimatsu by Iwamura Shokensai I (Tôkô, 1892-1968) [Fig. 23, 24, 25, 26]. This lovely girl is actually part of pair by Tôkô. Again, the face is very well done. But if we look we can see that in comparison with the Katsumitsu doll, the creases around the nose are a little less sharp, the eyebrows are more finely painted with individual lines radiating inwardly, and a little more attention paid to the eyelids with the eyes deeply set. Her face, while smiling and pleasant, is a bit more subdued, which is very much in keeping with the Shokensai tradition, having trained initially as a carver of Buddhist sculpture.

Now, to take it to the “best” level, let’s look at the final example from Hirata Gôyô II (Tsuneo, 1903-1981) [Fig. 27, 28, 29]. This doll is actually a jiyû-ningyô, more closely paralleling a BJD construction, rather than a soft-jointed ichimatsu. Here we see a much higher level of realism. The folds around the eyes and nose are done very naturalistically, the eyebrows show the same inwardly radiating brush strokes, but are much more fine. And here, real hair eyelashes are included rather than the painted ones from the previous example. The gofun has been worked to a closer approximation of natural skin tone, with pink-flushed cheeks. The mouth, also, has a slightly pursed aspect, very skillfully executed, not formalized or completely balanced and symmetrical. Of course, Gôyô was the first doll Japanese doll artist to be designated as a living National Treasure, so one would expect the best of him.

In continuing our review of qualities to look for in evaluating ichimatsu, we can’t just stop at the face, but we need to look at the hands and feet as well as indicators of quality.

Hands/Feet: In terms of doll artistry and determining the overall quality of a doll, the hands and feet are also an important indicator. Although typically the better doll artists executed both the faces as well as the hands and feet, this is not always the case and therefore a good, better or best head does not always have commensurately high quality hands and feet to go with it.

In terms of hands, we are looking for delineation of fingers, naturalness of hand shape, and the inclusion of details. The poorest quality dolls typically have club hands, with no attempt to create fingers at all. As you slide up the scale of quality, the hands become more lifelike.

Let’s take a look at three hands, good, better and best, that help illustrate this.Our “good” hand is from an ichimatsu by Koryûsai [Fig. 30, 31, 32] Each of her fingers is well delineated, with the addition of painted fingernails. There is a certain sense of plumpness and a slight contour or undulation to the fingers giving them some feeling of life. Note the sharp v-channel at the top of each finger separation. This is typical of Koryûsai’s more general dolls and a quick shorthand identifier when looking at ichimatsu.

Now a second example comes from an ichimatsu girl bearing the kotobuki “high quality” level mark from the Kyoto atelier of Maruhei Ohkiheizô, and shows a higher level of sophistication. [Fig. 33, 34] These, “better” fingers are even more separated and individualistically rendered, with dimples at the knuckles, etched creases at the joints. And, rather than painted, the fingernails are carved and painted in a technique known as tsumekiri. The back of the hand is very well rounded, giving a greater sense of fullness. In addition the fingers are slightly bent, rather than stiffly straight, feeling natural and relaxed.

Our “best” hand comes from an exceptionally tall ichimastu girl by Shokensai. [Fig. 35, 36, 37] Here the fingers are nearly completely individualized with deep separation, particularly the index and pinky. We see the tsumekiri fingernails, with sharply defined nail walls and cuticle, and some lighter pigment to simulate the lunula at the base of the nail. The hand also has the knuckle and joint creases on the back as well as the palm side of the hand. I am including both left and right hands images here, because the right hand is truly exceptional and a bit inexplicable.

The right hand is depicted slightly closed, as if holding an object, a fan perhaps.

By tradition, Tokyo made ichimatsu always have their hands depicted flat, or relaxed, with only a slight flexion of the fingers. Kyoto made dolls, however, typically have their right hands holding a fan. That a Tokyo artist made a doll with a Kyoto-style hand is indeed unusual and intriguing. But the naturalism with which both hands are rendered point to Shokensai’s mad skill sets.

We’ve looked at condition. We’ve looked at faces. We’ve looked at hands. But don’t forget the feet–these can be the really telling difference between good, better and best in ichimatsu-ningyo.

Beginning with the Friendship Dolls of 1927, it became almost universally standard practice to place tabi socks on the feet of ichimatsu, both girl and boy dolls. Prior to this they were always depicted bare footed. Though covered by tabi, the good, better and best doll artists always treated the feet with the same level of attention they gave their hands.

But we will start with a doll by Saiki Tôgyoku. Tôgyoku was a prominent artist beginning in the Meiji Era and continued in popularity through the Taisho Era and was a very influential maker in determining the look and feel of ichimatsu girls. This girl was made when dolls were generally rendered barefoot. [Fig. 38, 39, 40] The toes are all well formed, but with no toenail details or separation of large and small toes.

Next is an example of another girl by Shôkensai, with her tabi on her right foot and her left foot bare. [Fig. 41, 42, 43] We can see the separation of the big toe that allows the tabi to be worn naturally. We can also see the tsumekiri treatment for the toenails, carved and painted. There are also knuckle indications and clearly individuated toes. But they remain a bit stiff and formalized.

Now compare this to the right foot found on a boy doll by Takizawa Koryûsai II. [Fig. 43, 44, 45, 46] The toe separation for the tabi is less dramatic, more naturalistic. The feet also have a rounder, fuller sense, and the nails are much more realistically rendered with attention to the nail walls, and inclusion of the lunula.

In essence, when examining the feet, all of the qualities described above for the hands stay consistent in determining good, better, or best.

In our on-going discussion on evaluating ichmatsu-ningyo we now turn our attention to textiles.

Thus far in this short series we have looked at condition and fundamental carving elements that help us to evaluate an ichimatsu-ningyô, determining where it falls in or Good/Better/Best range of quality.

Now, let’s turn to the textiles. This is the hook that first really got me interested in Japanese dolls as a whole. Due to the display practices for many types of dolls in Japan, they frequently remain out for only short periods of time and can spend the vast majority of their “lives” in storage boxes, utterly shielded from damaging sunlight and corrosive dust. Therefore it is not uncommon to find 18th century ningyô with near-mint textiles. This is a rare opportunity to see, enjoy, and inspect very fine textile art that is centuries old that is less readily preserved in other media.

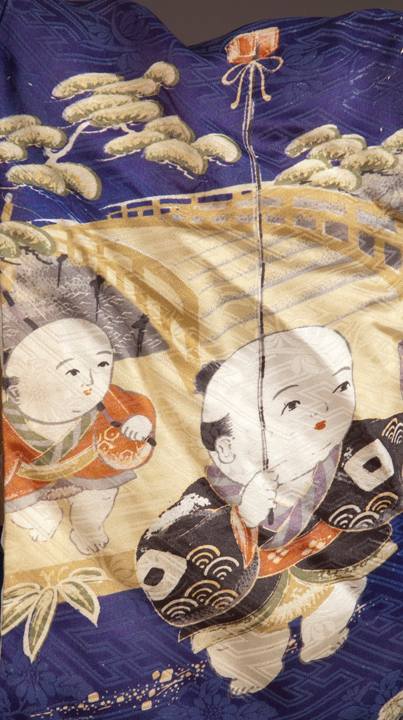

While ichimatsu as a genre originated only(!) in the late 19th century, here too we can find truly marvelous examples of the weaver’s art, immaculately preserved, beautifying the doll it graces and pleasing to our eye as we take in its details. [Fig. 44]

Textiles: For many collectors of Japanese dolls it is the textiles that truly set them apart from Western dolls. The exceptional quality of Japanese silk, the bold patterns and color combinations, the supplemental embroidery with the inclusion of gold or silver couched thread, the vibrant brocades of the elaborate obi tie belts with their fantastic bows at the back, the long flowing sleeves with additional under layers peaking out at the cuffs, all speak of luxuriousness, and to the Western eye, an undeniable sense of the exotic. This is not your grandmother’s Effanbee! [Fig. 44a]

Girl ichimatsu, particularly those created after the Friendship Doll exchange, are usually depicted in their most formal attire. This includes a furisode long-sleeved kimono, obi tie belt, along with various accessories: hakko-seko purse, fan, etc. But we cannot become distracted by the attractiveness of this attire in general, we have to look closely at the quality of the textile itself. This takes a bit more practice. All of our good, better, best ichimatsu will be wearing gaily patterned silk. But some of this is printed silk, others are done through a more complex dyeing process known as yuzen, and the best will also include supplemental embroidery and family crests. Some silks are plain weave, others are figured, still others are of a fine silk crepe known as chirimen.

Our good textile is revealed on an ichimatsu boy by Katsumitsu. We saw his sister doll above, so we know she is of very good quality. [Fig. 45, 46, 47] The textile is done in a painterly manner with images of a gosho-ningyô procession along the Tôkaido Road, extending from the great Nihon-bashi Bridge in Edo/Tokyo all the way to Kyoto, passing below the slopes of Mt Fuji. The scenes in and of themselves are delightful, the plain weave silk done in a strong blue. But the silk is a printed silk. However fine, printed silk will always be only a “good” option.

Now let’s compare this to a yuzen-dyed kimono also featuring a number of design elements ranging from floral bursts to curtains of state to straw-roofed huts. The silk is a fine chirimen, silk crepe [Fig. 48, 49] This comes from a “better” ichimatsu girl by the artist Eitokusai III (Yamakawa Yasujirô, 1864-1941). We can see that the base fabric is a high quality chirimen silk crepe and that, rather than printed, all of the patterning is done through the much more sophisticated and labor-intensive yûzen paste-resist technique. There is also additional layering with a fawn-spot inner layer visible at the sleeve openings, which have been tied closed with red silk threads, that adds an even additional element of care and sophistication when looking at the kimono quality.

Now let’s again compare these to the kimono for a “best” category doll. Here a spectacular ichimatsu by Hirata Gôyô II wears a light green yûzen dyed chirimen kimono bearing family crests at the shoulders, elbows and the back of the neck, five in all as befitting the kimono of a girl of position. [Fig. 50, 51] All of the design elements are rendered in a painterly way, and, in addition to our more typical flower motifs, we also find field curtains and noblemen in court regalia enjoying an outing. Silver foil thread helps to form cloud like bands and gold foil is used to pique out the center of the floral blossoms. [Fig. 52].

And finally in our series we turn to the artisans/artists that made these amazing examples of doll art, and what role they play in determining good/better/best in ichimatsu-ningyô.

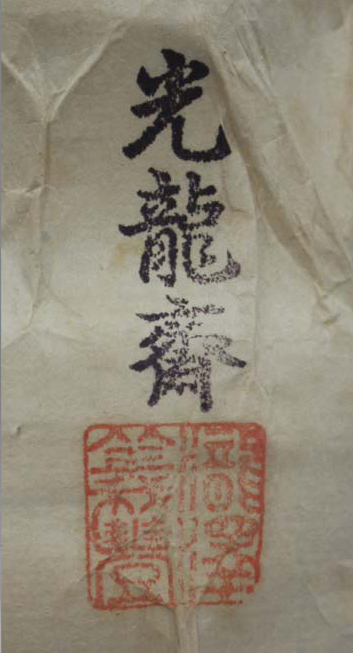

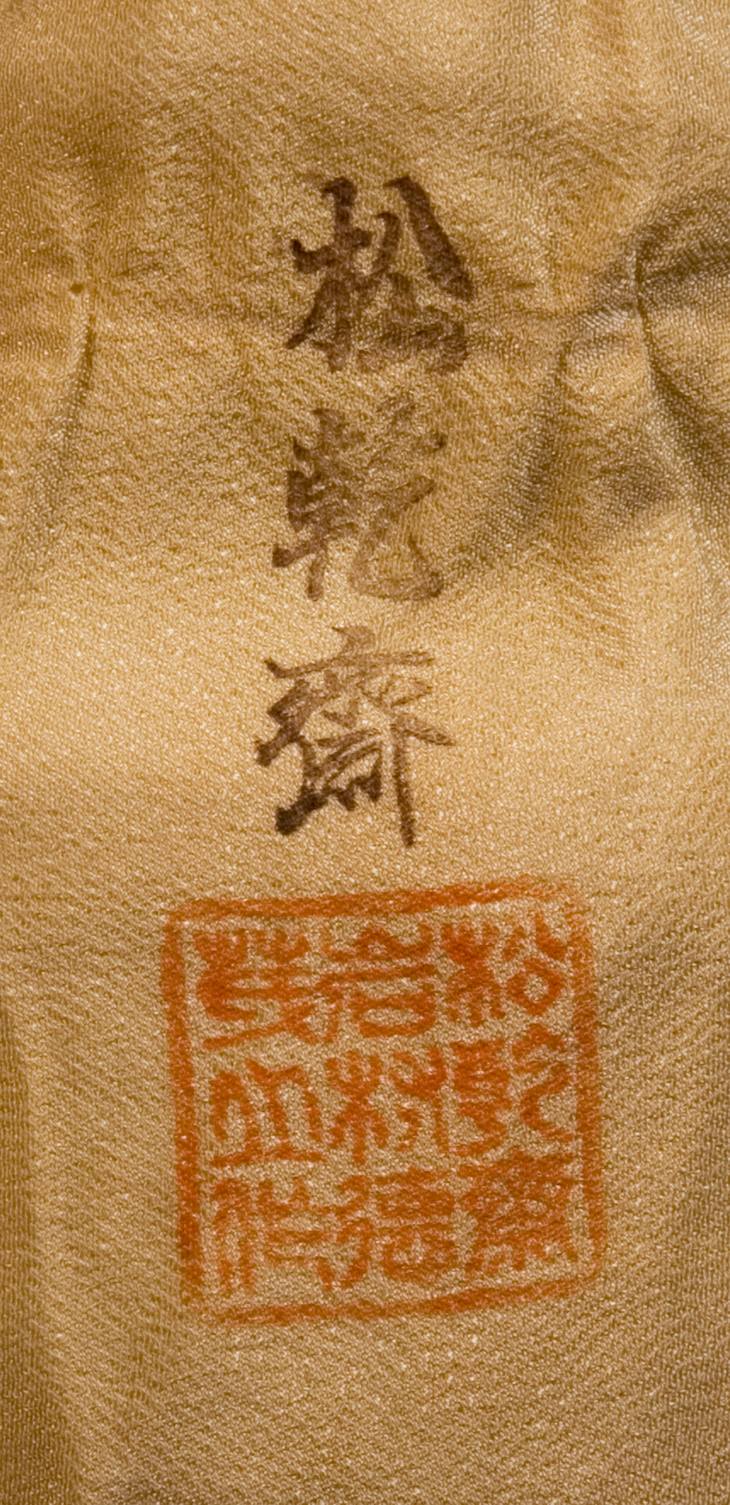

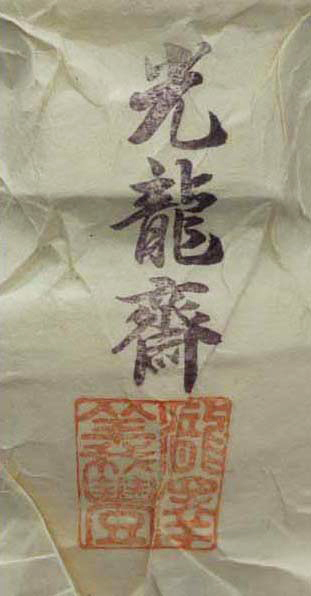

Historically, Japanese doll makers worked in anonymity, the proverbial unknown craftsman. [Fig. 53] The ateliers they worked under frequently sold and marketed their pieces under the shop name only. Periodically, a specific artisan might emerge that became a selling point in their own right. Sometimes the artisan was also a shop owner and direct marketer and thus their names are better preserved in the historic record. This record is generally preserved in their original storage boxes which frequently lists type of doll, date of its making, seasonal references, the maker, and, occasionally, the original owner. [Fig. 53a]

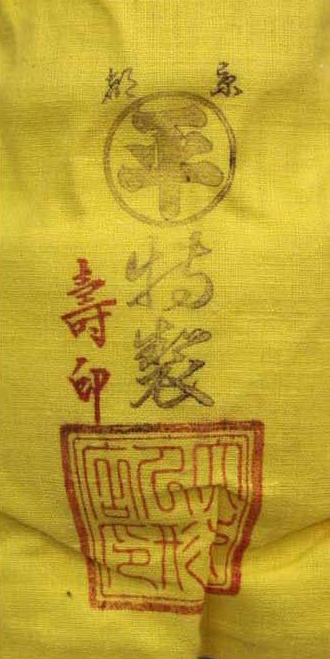

Beginning in the late 19th century, however, a new tendency among doll makers, particularly those working in the daki-ningyô and ichimatsu-ningyô areas, was to start signing their dolls by placing a paper or silk wrapper around the doll’s waist underneath the kimono. These are called a dôgami (body paper), and frequently included the artist’s shomei (signature) and his rakkan (seal). The seals become important as they frequently changed over time and a careful study of them can helpful in dating a doll within the arc of a given artist’s career. [Fig. 54, 55] I include an extensive index of artists along with the various signatures and seals in my book: Ichimatsu: Japanese Play Dolls ( https://www.antiquejapanesedolls.com/…/ichimatsu… ) [Fig. 56]

Artist: The final category that I look towards in my evaluation of ichimatsu is that of the artist: who actually made the doll. A unique component of most ichimatsu of good, better, and best quality is the inclusion of the dômei “signature cloth” around the waist underneath all of the clothing. [Fig. 57] This signature cloth frequently bears the name and seal of the doll artist, and sometimes the shop selling the doll. This is important information for the doll collector to know, for artists (as well as atelier) also help influence value.

Early important artists for ichimatsu collectors to know and look for include: Takeuchi Masujirô (c.1860-1941), [Fig. 58] and Saiki Tôgyoku (active late 19th -early 20th century) [Fig. 59] are two influential early makers based in Tokyo who did much to help define the look of 20th century ichimatsu. Hirata Tsunejirô (Gôyô I, 1878-1924) was also extremely influential, creating his own unique blending of hyper-realism with a stylized appeal. [Fig. 60] Catalogs dating from the late 1920’s and 1930’s printed by Yoshitoku Doll Company in Tokyo featured dolls by representative artists without clothing, revealing their signature cloths. [Fig. 61] Prices were also listed. Artists such as Gyokusui, Shunsui, Okoku, Shogetsu, and Kinsei, among others, established their reputations as fine ichimatsu makers through their associations with Yoshitoku. By contrast, important Kyoto ateliers such as Maruhei Ohkiheizô and Namikawa, shielded the names of their participating artists and their signature cloths frequently only bear their shop logo and quality rankings. [Fig. 62]

In general, however, the most important ichimatsu artists were those that participated in the 1927 Japanese Friendship doll exchange. [Fig. 63] This historic exchange not only raised the popularity of ichimatsu around the world, it also help to elevate their artistry. Nine artists were selected to participate in this event from Tokyo, and I provide detailed biographies where possible in my book: Art as Ambassador: The Japanese Friendship Dolls of 1927. [Fig. 64, 65]

But for our purposes here, the three most important artists to remember and look for are: Iwamura Shôkensai (Tôkô, 1892-1968) [Fig. 66, 67], Takizawa Koryûsai II (1888-1966) [Fig. 68, 69] and Hirata Tsuneo (Gôyô II, 1903-1981) [Fig. 70, 71]. We have seen examples of all three in the discussion above. The fame and reputation of these three artists in particular elevated them to the very top of the ichimatsu market and their works became highly sought after. Shôkensai, also known as Tôkô, and Koryûsai largely dominated the industry, focusing almost exclusively on the creation of ichimatsu for both the general and more specialized, high-end market throughout the rest of their careers. While Gôyô, along with his young brother Yôko (Hirata Yôko, 1906-1975) [Fig. 72, 73], took his new-found popularity and used it to promote the sosaku-ningyô (art doll) movement, fighting to have doll artisans properly recognized as artists. He was rewarded for his efforts by becoming the first doll maker to be designated as a ningen kokuhô (Living National Treasure) in 1955. [Fig. 73a]

To conclude I would like to shift gears and use three boys that I feel are all “Best” in their own way. Each is in mint condition; each has wonderful face, hands/feet; amazing kimono; and each bears the hallmarks if not the signature of significant artists.

First is this amazing unsigned boy ichimatsu that has all of the elements we are looking for: exceptional condition, exceptional face and hand modeling, exception textiles, are all immediately apparent. The surprise for me when I found this piece is that it is unsigned. It bears all the hallmarks of the Gôyô lineage in terms of the quality of the face and the slightly folded fingers with exceptional detailing throughout, but is lacking a signature cloth. [Fig.74, 75, 75a, 76].

Next is a spectacular boy by Koryûsai. He is actually part of a glorious large-scale pair. He wears a formal black haori outer jacket with an impressive design of flying cranes, each piqued out with supplemental embroidery. It bears the katabami word sorrel crest of the family that commissioned him. His face is classic Koryûsai with a bright and happy expression, with finely wrought features that includes real eyelashes. Hands, as to be expected, are naturalistically rendered with tsumekiri fingernail details. His painted hair is done evenly and his exposed ears are done with a high level of naturalism. And his dômei bears the signature and seal of Takizaku Yoshitoyo (Koryûsai II). [Fig. 77, 78, 79, 80] His female companion is equally fabulous and I share a few images of her here. [Fig. 81, 82, 83]

And although NADDA is exclusively an organization focusing on antique dolls, my final example is actually from the contemporary ichimatsu master maker, Fujimura Kokan (b. 1953).

I do this intentionally as the art of the ichimatsu-ningyô was nearly lost after the WWII, when economic challenges and a need to replace so many lost dolls resulted in a tremendous and tragic downgrading in the skill sets of the ichimatsu makers who, by necessity, had to sacrifice quality over volume.

Fukimura Kokan has been instrumental in establishing a group of Tokyo-based makers dedicated to restoring the highest level of artistry to their dolls. Kokan’s work with gofun, though in a decidedly modern vein, captures the beauty and elegance of this very difficult material. Similarly, he employs only the finest textiles, frequently taken from antique kimono to adorn his dolls, adding to their elegance and desirability.

So here I present a contemporary ichimatsu boy that Kokan has entitled: Waka-danna (Merchant’s Son). In this piece, all of Kokan’s skills are clearly in evidence, from the detailing of the face with its lustrous gofun, the arrangement of the hair in a complicated Edo style for young men, to the articulation of the fingers which he has accentuated on the left hand to allow him to hold a small money purse. The feet as well, show the same level of detail. His haori jacket is taken from an antique chirimen silk crepe kimono bearing a sophisticated scholar’s table motif with writing implements, scholar’s rock and incense. Simply the best of the modern ichimatsu makers. [Fig. 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89]

I trust you have enjoyed this brief(!) series on Good. Better. Best. A convenient tool for beginning to understand the quality differences between those Japanese ichimatsu dolls that “all look alike.” [Fig. 90]

If you liked this series you might want to look at my YouTube video on this topic which goes into greater depth with even more images: [Fig. 91, 92]

Rachel Hoffman and Diane Hoffman’s Doll Collection

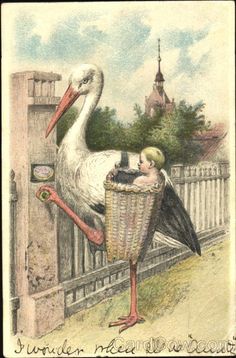

For generations, the stork has been a symbol of new life and family blessings. This endearing tradition dates back to ancient mythology and folklore, with several cultures citing the bird as a harbinger of happiness and fertility. The story gained widespread appeal in the 19th century through Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale, “The Storks,” which depicted storks delivering babies to homes.

This whimsical tale was likely a gentle way for parents to explain the arrival of a new sibling to children. The image has endured through the ages, becoming a classic representation of birth and the joyous arrival of a new family member. The stork’s poised, nurturing image, gently ferrying an infant bundled in cloth, has become a symbol of the timeless joy and wonder of family growth.

Today, this charming figure of the stork carrying a newborn continues to evoke warmth and affection, a reminder of the precious moments of life that our dolls often seek to capture. This particular stork, carrying its precious bundle, was a beloved piece in my mother, Diane Hoffman’s collection. It now stands as a cherished part of our doll shop, representing the legacy of love and the cycle of life that dolls encapsulate so beautifully.

We, at Turn of The Century Antiques, are proud to preserve and share not just this piece of history, but the countless stories that each doll in our collection holds. May they continue to bring joy and a sense of wonder to our lives.

The Toni Doll by Ideal Toy Company has been a beloved figure in the world of doll collecting since its introduction in the late 1940s. These dolls were groundbreaking for their era, featuring washable hair that could be styled, and they often came with their own “Play Wave” kit. Toni dolls were crafted to reflect the American beauty standard of their time, with their sparkling eyes and stylish outfits.

This array of Toni dolls holds a special place in our hearts and on our walls. It was assembled for a very memorable visit from the renowned doll artist Robert Tonner in 2021. Robert, with his exquisite eye for doll artistry, is not just a creator but also a collector himself. Fun fact: he has a passion for vintage dolls, including the delightful Toni dolls, which reflects his deep appreciation for the rich history of doll craftsmanship.

The Toni dolls here not only represent a chapter of doll history but also remind us of the connections and friendships we’ve forged in the doll-collecting community. It’s a testament to how dolls can unite people, celebrating shared passions and creating lifelong friendships.

As we continue our virtual tour of the doll shop, we step into the heart of creation and care – our doll repair department. Here, nestled among the tools and threads of the trade, sits a true classic: a Singer sewing machine.

Since its inception in the 1850s, the Singer Sewing Machine has been a staple in homes and businesses, a testament to the innovation of Isaac Merritt Singer. These machines revolutionized the textile industry and brought the art of sewing into countless households. The Singer’s sturdy construction and reliable stitching made it a favorite for all, from homemakers to professional seamstresses.

In the world of doll collecting, a Singer sewing machine holds a special place. It’s the silent witness to countless repairs, restorations, and creations of miniature garments that dress our beloved dolls. Each stitch is a note in the symphony of doll collecting, where the love for craftsmanship and detail is as evident in the clothes our dolls wear as in the dolls themselves.

The Singer in our workshop not only serves a practical purpose but is also a nod to the history of sewing and the handcrafted charm that doll collectors cherish. It’s an emblem of the care we put into every repair, ensuring that each doll returns to its owner ready to be loved for many more years.

Join us in marveling at the Singer sewing machine’s legacy and its role in keeping the tradition of doll collecting vibrant and alive.

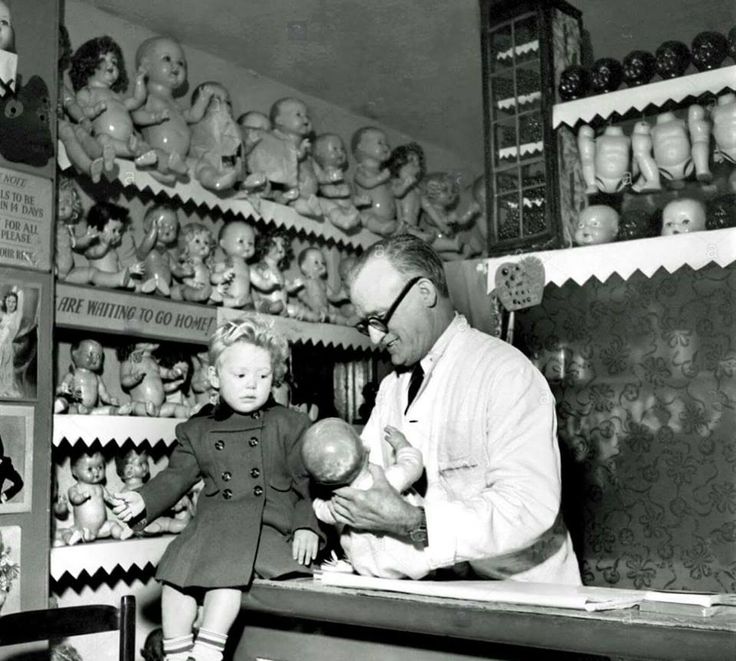

Step into the past with us as we explore the enchanting history of doll repair—a craft as old as doll making itself. This time-honored tradition has brought countless beloved playmates back to life, much to the delight of collectors and children alike.

The art of doll repair is deeply rooted in our collective history. As early as the 1800s, “Doll’s Hospitals” began appearing, first in Europe and then spreading worldwide. In these magical places, skilled artisans, much like the caring professionals in a real hospital, would mend broken limbs, refresh worn faces, and replace tattered clothing.

These images from a bygone era capture the essence of the doll hospital’s charm. From the expert hands of a repair artist to the hopeful eyes of a child waiting for their treasured companion’s return, these snapshots remind us of the timeless bond between us and our dolls.

Our very own doll repair department continues this legacy with pride. We not only mend and restore, but we also preserve the stories and memories woven into each stitch and seam. In our hands, dolls are not just playthings but treasured keepsakes, carrying the legacy of those who loved them before. You can see a lot of our old doll repair videos on YouTube; search “repair,” and you will see some great videos with Linda! https://www.youtube.com/@RachelHoffmanDolls

You can also find a list of doll hospitals on the Madame Alexander website (scroll to the bottom): https://madamealexander.com/doll-care/

Let’s celebrate the craftsmen and women, past and present, who have made it their life’s work to ensure that no doll is ever beyond repair, and every doll has the chance to be cherished once again.

Doll stores have been enchanting spaces for collectors and children alike since the 19th century. With the advent of industrialization, dolls transitioned from being handcrafted at home to being mass-produced, giving rise to dedicated doll shops. These shops were not just places of commerce but wonderlands where fantasy met reality. They became cultural staples in cities and towns, enchanting passersby with their displays of miniature beauty and artistry.

The evolution of doll stores reflects the changing trends in society, from the porcelain beauties of the Victorian era to the introduction of character dolls in the early 20th century, and eventually to the iconic fashion dolls of the 1950s and beyond. Each era’s doll stores offered a window into the contemporary world, dressing dolls in the latest fashions and often becoming trendsetters themselves.

Our very own shop is a tapestry of this history. Here, amidst our curated displays, we not only sell dolls but also continue the tradition of being a space for community and shared joy. We are a part of a legacy that has brought joy, comfort, and a touch of the fantastic to daily life for over a century.

This photograph captures the essence of our shop’s spirit—a place where each doll tells a story, and every shelf holds a piece of history. We are proud to be part of this ongoing story, connecting past to present, and we invite you to continue to create beautiful memories with us.

Bild Lili, the stylish German fashion doll, was originally produced from 1955 to 1964. She was based on a comic-strip character and swiftly became an icon of her era, embodying the chic, independent woman of the 1950s. Lili was not initially intended for children; instead, she was a novelty item sold to adults in bars and tobacco shops. With her hourglass figure and a wardrobe fit for any high-society event, Lili became a sought-after collector’s item.

Interestingly, Lili’s design would later inspire the creation of the world-famous Barbie doll, which debuted in 1959. Barbie would go on to become a household name, leaving an indelible mark on the toy industry and pop culture.

The Bild Lili doll in our collection was more than just a toy; she was a treasure trove of history and style, a reminder of the doll’s evolution through the ages. While we cherished her presence in our store, she now resides at La Casa de las mil Muñecas in Mexico City, continuing to delight and educate visitors about her rich and fashionable legacy.

Step back in time with us to 1959, as we highlight a true jewel from Diane Hoffman’s esteemed collection at Turn of the Century Antiques—a Number One Barbie doll, an inaugural piece that sparked a global phenomenon.

This doll isn’t just a toy; she’s a piece of history. As the first of her kind, Number One Barbie introduced the world to a new era of play and imagination. With her distinctive features, like the iconic ponytail and arched brows, she was a departure from the baby dolls that dominated the market. Barbie was a trailblazer, reflecting a more grown-up, glamorous life that little ones could dream about.

Dressed in the luxurious “Gay Parisienne” outfit, complete with a puff-sleeved navy cocktail dress adorned with white polka dots and accessorized with a faux fur stole, this Barbie epitomizes the elegance and style of the late 50s. The “Gay Parisienne” is one of the rarest and most sought-after Barbie outfits, making this doll an even more precious member of our collection.

This cherished doll continues to be admired by collectors and enthusiasts who visit us, each captivated by her grace and story. She’s more than just a part of our collection; she’s a beloved member of our doll family, embodying the legacy of passion and preservation that Diane Hoffman championed throughout her life.

Come visit to take a closer look at this classic beauty and the countless other treasures that live within the walls of Turn of The Century Antiques. Every doll has a story, and we’re eager to share it with you.

Captured here is a rare Oscar Hitt Googly doll, a cherished favorite of Diane Hoffman. Its whimsical expression and unique charm reflect the joy and depth found in doll collecting. Here are 10 reasons why doll collecting is an incredible hobby:

Historical Connection: Dolls are pieces of history that capture fashion, culture, and art from different eras, allowing collectors to hold a piece of the past.

Artistic Appreciation: Collecting dolls involves an appreciation for the intricate craftsmanship, from hand-painted features to hand-sewn garments.

Emotional Bond: Dolls can evoke nostalgia and warmth, creating a sentimental link to childhood or cherished memories.

Educational Value: Doll collectors often learn about the historical context of their dolls, including the periods they represent and the stories behind them.

Community and Friendship: Collectors join a community of like-minded enthusiasts, sharing their passion and forming lasting friendships.

Preservation of Craft: Each addition to a collection helps preserve the fine skills involved in doll-making, often passed down through generations.

Investment Potential: Many dolls, especially rare finds like the Oscar Hitt Googly, can increase in value, making doll collecting a potential financial investment.

Therapeutic Effect: The hobby offers a therapeutic retreat, providing a creative outlet and a calming influence.

Cultural Diversity: Collecting dolls from around the world offers insight into different cultures and their unique artistic expressions.

Legacy Building: For many, like Diane Hoffman, doll collecting is about building a legacy that can be passed down and enjoyed by future generations.

As we appreciate this Googly doll’s playful gaze, let’s recognize doll collecting as a hobby that is as rewarding as it is delightful.

As we continue our delightful April takeover on the NADDA page, we turn our attention to the romantic and elegant world of wedding-themed dolls. The ones featured here are splendid Madame Alexander wedding party dolls from the cherished collection of Diane Hoffman at Turn of the Century Antiques.

Wedding-themed dolls have graced collections for generations, reflecting the customs and fashions of their times. Since the 1950s, these dolls have celebrated the beauty and ritual of marriage ceremonies, with intricate bridal gowns and meticulously tailored suits that capture the essence of the joyous occasion. They often serve as cherished mementos of one of life’s most significant milestones.

Madame Alexander has been at the forefront of this tradition, creating wedding party dolls that are sought after for their exquisite detail and craftsmanship. Each doll, from the blushing bride and groom to the adorable ring bearer, is a masterpiece, encapsulating the grandeur and emotion of a wedding day.

Diane Hoffman’s eye for exceptional pieces has brought together this stunning ensemble, which continues to be a centerpiece in our store. They stand as a testament to the lasting union between artistry and the celebration of human experiences.

This April, as part of our NADDA page takeover, we’re proud to spotlight a distinguished member of our collection at Turn of the Century Antiques—the vintage Ring Bearer doll by Madame Alexander.

The tradition of ring bearers is a long-standing one, dating back to ancient Egypt, where valuables were often carried on ornamental pillows during important ceremonies. This role became a staple in wedding customs, symbolizing the delivery of the couple’s promises to one another. The role of the ring bearer, traditionally a young boy dressed in his finest, is to carry the wedding bands to the altar, heralding the imminent vows with sweetness and solemnity.

Madame Alexander, esteemed for their finely crafted dolls that capture the spirit of their times, lovingly crafted this Ring Bearer doll. With his crisp suit and earnest expression, he brings to life the pageantry and joy of the wedding tradition in miniature form.

Rest assured, this charming little fellow is still with us, bringing joy and a touch of nostalgia to everyone who visits Turn of the Century Antiques. He is a beloved piece, symbolizing the joyous beginnings that weddings represent and the meticulous craftsmanship of Madame Alexander dolls.

I’m honored to share a more in-depth look into the storied history of the Madame Alexander Doll Company, alongside some of the exceptional pieces from my mother, Diane Hoffman’s collection at Turn of the Century Antiques.

The Madame Alexander Doll Company was born out of the vision of Beatrice Alexander, a woman who grew up surrounded by dolls in her father’s doll hospital in New York City. She started her company in 1923, and it grew from a small family-owned business to an internationally recognized brand, synonymous with quality, innovation, and an unwavering commitment to craftsmanship.

Beatrice, known professionally as Madame Alexander, was a visionary in the field. She recognized early on that dolls could be more than just children’s playthings—they could be a medium for artistry and storytelling. She introduced dolls with characters, giving them backstories and personalities, and setting the stage for play that was both imaginative and instructive.

Madame Alexander was the first to produce dolls representing characters from literature, such as “Alice in Wonderland” and “Gone with the Wind.” Her company gained fame for the “Scarlett O’Hara” doll during the height of the movie’s popularity. The company also pioneered ‘sleep eyes’ in dolls, which could open and close, rooted hair that could be styled, and dolls with bending knees.

Over the decades, the company has celebrated historical events, cultures around the world, and even created dolls in the likeness of living people. Each creation is a piece of a larger narrative, one that honors the fabric of our shared experiences.

The Madame Alexander Doll Company remains a beacon of the American dream, proving that with innovation and passion, a small family enterprise can leave an indelible mark on the world.

The dolls you see here from Diane Hoffman’s collection are not just masterfully designed; they also represent the heart and soul of a company that has brought joy and inspiration to generations of doll enthusiasts.

Let’s delve into the heartwarming history of Raggedy Ann and Andy, showcased here as RARE “Oversized” dolls by Volland, cradling a portrait of Diane Hoffman by Diana Vining.

Raggedy Ann first captured hearts in 1915, created by American author Johnny Gruelle for his daughter Marcella. The doll, with her red yarn hair and triangle nose, became the protagonist of Gruelle’s stories, which were published in 1918 to instant acclaim. Raggedy Ann was patented that same year and the dolls began production by the P.F. Volland Company as storybook companions.

Raggedy Andy, her equally lovable brother, joined the family in 1920, sporting a sailor suit and a contagious spirit of adventure. Together, the dolls became a symbol of childhood innocence, imagination, and enduring love. Their simple, yet expressive features and soft construction made them comforting companions and their popularity soared.

These “Oversized” Raggedy Ann and Andy dolls are exceptional examples of the early craftsmanship of Volland dolls. Standing much larger than the standard dolls, they were likely made for display purposes, adding to their rarity and charm.

The portrait they hold of Diane Hoffman, expertly crafted by artist Diana Vining, is a testament to Diane’s own legacy as a celebrated doll expert and beloved figure in the doll-collecting community.

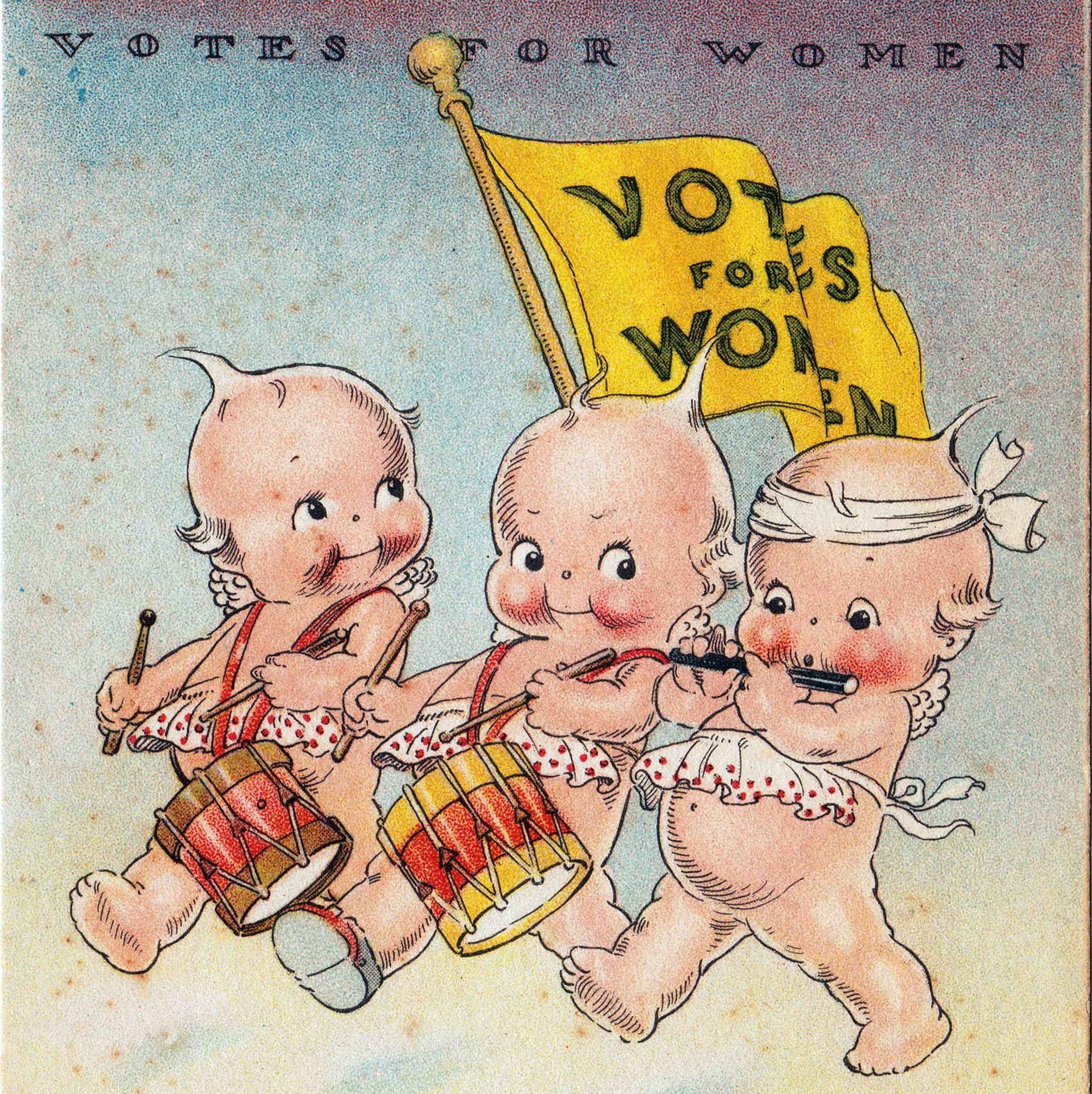

Step into the whimsical world of Kewpie dolls, an enduring classic that continues to capture hearts! Created by illustrator Rose O’Neill in the early 20th century, these cherubic figures first appeared in Ladies’ Home Journal as whimsical, cupid-like characters. They quickly soared in popularity, leaping off the page and into the physical world in the form of dolls first produced in 1912.

Kewpies were distinct with their impish smile, side-glancing eyes, and tuft of hair on top. They were not just playthings; they symbolized joy and kindness, which Rose O’Neill felt strongly about spreading. The dolls were originally made from bisque in the early years and later transitioned to celluloid and, eventually, vinyl and rubber, making them accessible to many.